POSITIONALITY STATEMENT

This paper was led by Dharug women and included contributions from two non-Indigenous cross-cultural ecologists, all affiliated with the University sector. We intended to take the reader on a cross-cultural learning journey culminating in the historic Dharug women’s-led cultural burn in Lane Cove National Park, northern Sydney, in May 2024. The women authors participated in that journey in a variety of ways. The work centred on the research question: How do we care for Country when Country is a city of 6 million disconnected people? In 2021, the research attracted the attention of then-named New South Wales (NSW) Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DPIE), who provided the opportunity for the first Dharug women’s-led cultural (cool-fire) burn in an inner-city national park since British colonisation in 1788. This resulted in an historic fabric of relationality being woven between the Dharug community, State and local government agencies, neighbouring corporations, Macquarie University academics, the general public, and Ngurra, through the local Dharug women’s ways of knowing, being and doing (Rey, 2021).

INTRODUCTION

In the context of global climate crises, this paper outlines the journey of a group of Dharug Aboriginal women towards restoring the ontological practice of caring for Country through cultural guwiyang (fire) on Dharug Ngurra, being the urbanised metropolitan area known today as ‘Sydney’, in so-called ‘Australia’. Dharug yiyura/people are the traditional custodians of the area. Evidence from European coloniser documents and charcoal/pollen deposits suggest that Dharug people and other clans across the Sydney Basin harnessed fire for multiple purposes, including to manage and care for Ngurra (Black & Mooney, 2007; Clark & McLoughlin, 1986; Jurskis & Underwood, 2013; Kohen, 1986; McLoughlin, 1998). However, Dharug guwiyang has been prevented in this landscape since European colonisation, resulting in significant ecological and cultural harm (Cahir et al., 2018; M.-S. Fletcher, Hall, et al., 2021; Mariani et al., 2022; Pascoe et al., 2023). Cultural fire (also known as ‘cultural burns’ or ‘cool-fire burns’), as a community relationship with Country, has been practiced in a variety of locations across the continent for millennia (Cahir et al., 2018; M. S. Fletcher & Thomas, 2010; M.-S. Fletcher, Hall, et al., 2021), producing the longest biocultural continuity on the planet (Gammage, 2011). Just as there is diversity across all the various ecosystems, landscapes, languages and Aboriginal communities of the continent, so there is diversity in cultural burning practices (Atkinson & Montiel-Molina, 2023; Pascoe et al., 2023; Steffensen, 2020). Rather than have a system of seeing fire as homogenous ‘other’ and a threat, with a set response determined primarily by ‘asset protection’, cultural burning is about sustainable relationality (Atkinson & Montiel-Molina, 2023; Neale et al., 2019). Cultural burning knowledge is not lost but can be nurtured back to Country again given the right spirit and care. ‘Burning Love’, as cool-fire-caring, protects, nourishes, and sustains sentience. Just as in the human realm of love and caring, where we understand that our wellbeing relies on the wellbeing of those we love, so in Aboriginal culture using cool fire is an act of love for kin (other-than-humans) and Country, for all sentient beings (Tynan, 2020).

‘Cultural Burning’ is becoming common terminology for the Aboriginal practice of caring for Country using fire, that differs from Western hazard reduction burns in a variety of ways (David et al., 2024; Pascoe et al., 2023; Penman et al., 2011). Unlike Western methods, cultural burning includes intimate deliberate actions, with acknowledgement of Country as kin, and ceremony as a cleansing preparation for participation. It does not just include a Review of Environmental Factors (REF) as designated by government agencies. Rather, the process of cultural burning includes and interprets the site through its relationship with Aboriginal Ancestors, spiritual continuity, and kin (Ngurra et al., 2019). Additionally, low flame height, white smoke, and much lower heat temperatures, set in mosaic format across the designated burn area are all typical elements of Aboriginal cultural burns, but those aspects do not make a recipe for replication (Atkinson & Montiel-Molina, 2023; David et al., 2024; Pascoe et al., 2023). Characteristically, it is said that low intensity fires give resident fauna a longer period to escape than hot fires, improving their likelihood of surviving (Jolly et al., 2022). Hot, intense fires, with black smoke, as seen in the 2019-2020 ‘Black Summer’ mega-fires in south-eastern Australia, can destroy all the habitat and can trap and kill the residents themselves (Metcalfe & Costello, 2021). Another difference involves the carbon cycle through plants, soil and air. Low intensity fires can nurture the soil by returning carbon to the soil (Country et al., 2024), evidenced as black ash; whereas high severity fires tend to burn the soil and reduce carbon (Granged et al., 2011), evidenced as white ash. High intensity fires generally emit more carbon to the atmosphere, likely exacerbating global warming and climate change issues (Bowman et al., 2021).

This project was precedent-setting for inner-urban areas, offering international Indigenous communities in other urban areas the wisdom of ‘Burning Love’ for the mutual benefits of all in a climate-crises context. Aboriginal names are adapted for cultural safety reasons. The project returns Dharug language, Dharug women’s knowledges, practices and care for our other-than-human residents, alongside Western ways of collecting ecological data. It involves localised activism, building human-other-than-human relationships, enabling localised connection, caring and a sense of belonging for allies, to the presences, places and Dharug people.

PART 1

A LEARNING JOURNEY

Jo Anne Rey

WALKING TOGETHER: Background and Journey towards the Dharug Cultural Burn

After three years of planning and deliberations, the time had come for Dharug cultural guwiyang (fire) to return to Ngurra, in what is now known as Lane Cove National Park, Sydney. It was a clear autumn morning on Dharug Ngurra. It felt good – peaceful and calm. The physical activation of our historic journey, returning Dharug cultural guwiyang to Walumadagal Ngurrang – the place and people of the Wallumai, the Black Snapper Fish - had begun, and the preliminary sessions of the planned cultural burn were underway. We were finally nearing our destination – a journey of determination, patience and persistence that Corie and I had shared since July 2021.The history of this journey came about because of people yarning/talking/storysharing and walking with Ngurra – Her presences, places, and people.

A Yarning ‘Their-Story’

Jo received a Macquarie University (MQU) post-doctoral Fellowship in Indigenous Research (MUFIR) in July, 2020 for the project: ‘Weaving Country across the City: Activating Dharug Ngurra’ (Rey, 2023).

The purpose of the MUFIR was to show how Dharug Ngurra was being activated through cultural practice from the outer reaches of Sydney (Shaw’s Creek Aboriginal Place, on Boorooberongal people’s land of Dharug Ngurra;) across the middle suburbs (Blacktown Native Institution site, at Plumpton) and almost into the inner-city at the Badhu Nuru (waterhole), also known as Brown’s Waterhole, in the Durumbura Dhurabang (Lane Cove River and National Park). In 2020 I didn’t really know how this was going to play out, but I felt confident it could.

It was the third site, beside the Badhu Nuru, that became the place of ‘Burning Love’ and where the restoration of Dharug women’s-led cultural burn took place. It was here that the activation drew Dharug knowledges, practices, materials and people across Country-as-City. This was possible because of the ongoing Dharug presence, with cultural gatherings and cultural practices happening particularly at Shaw’s Creek, where cultural burns continue (Ngurra et al., 2019). The proposed new burn site was on the Walumadagal side of the Durumbura river, in Dharug Ngurra/Country. So, with the MUFIR project established, the yarning started. One day, the lead Jo went with my research assistant, and Pairrebeenne Trawlwoolway woman, Lauren down to Brown’s Waterhole, and discussed how the banks badly needed a cultural burn. This was not based on anything more than a recognition of the dense undergrowth and weeds, which once dried out, could fuel a future megafire. Memories of the devastation caused from the 2019-2020 ‘Black Summer’ fire catastrophes, that engulfed the south-eastern portion of the continent now called ‘Australia’, were also still fresh (Gallagher et al., 2021).

Lauren agreed and, as she was interested in looking at cultural fire for her doctoral research, she informed me of her connection with the NSW State Department of Planning, Industry and Environment’s (DPIE) ‘Cultural Fire Management Unit’ (CFMU) (Tynan & Cavanagh, 2021). This team was led by Vanessa (Bundjalung and Wonnarua woman) and Uncle Nook (Yuin Walbanja man). Vanessa also was doing her doctorate on Aboriginal women’s-led cultural burn practices (Cavanagh, 2022).

Shortly afterwards, Lauren contacted me to say she had spoken with the CFMU about my project, and very soon I was contacted and asked if I would be interested in engaging with Vanessa’s research project by developing a Dharug women’s-led cultural burn at Brown’s Waterhole. Let’s say I felt an activation on the horizon.

Yarning-up Ngurra: First Steps

The journey towards the Dharug women’s-led cultural burn began with listening and yarning. Early conversations with Dharug and neighbouring fire practitioners affirmed the cultural significance of Browns Waterhole and its suitability for a cultural burn. An initial assessment suggested that the landscape near the waterhole could support a cool burn, renewing both the Country and its relationships. For a Dharug women’s burn to proceed, it was essential that Dharug women themselves assess the site. A Dharug-led site visit, supported by a Dharug fire practitioner and attended by representatives from the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and the Department of Planning and Environment (DPE), affirmed that the journey toward cultural burning could begin. NPWS is committed to assisting with the procedural requirements, including preparing the necessary documentation to align with government frameworks, while ensuring that Dharug women’s leadership and cultural protocols remain central.

To support the work, funding was directed to Yanama Budyari Gumada (Walk with Good Spirit) Aboriginal Corporation (YBG), the community-led organisation responsible for cultural governance. Macquarie University auspiced the funds to enable the project’s delivery. Formal preparations began on 1 July 2021, marking the start of a significant journey to return cultural guwiyang to Ngurra in the spirit of patience, humility, and respect.

Weaving Country across the City: Ngurra, Networking and Navigating a Path.

Of course, straight up, unprecedented difficulties arose. It was almost like Ngurra was testing our determination. With the context of COVID and people being in quarantine, it meant the ‘doing’ was delayed. Added to that, were the summer floods of 2021 and February 2022. It was very hot and very wet, and the ground cover was growing rapidly. At the start, the Daynya (Dodonaea triquetra) at the burn site was knee height. In May 2023, it was taller than we were!

Nevertheless, while the physical activities couldn’t start, it gave us time for planning, prepping, and networking. We developed our journey as involving three separate phases. First, growing the network of Dharug women and interested stakeholders was necessary. We called ourselves ‘DWACFA’ – Dharug Women and Allies Cultural Fire Association. While sounding a bit ‘ducky’, it gave us a title, and the name has survived the journey to date.

Secondly, we wanted a women’s camp to re-connect Dharug women with the site. Colonisation has meant Dharug have been separated from Ancestral places of connection, caring, and belonging, so bringing those connections back by physically being present-in-place is critical for regenerating culture as well as activating a cultural burn. Across the camp days, there would be three workshops. One, involving collection of materials for art practice, led by Dharug artist, Venessa-Possum and creating material-dyed scarves. Also, because we live in the 21st century, and we avail ourselves of today’s tools – the second workshop involved digital data collection software, (training by Em, MQU) which focussed on the Presences (the other-than-humans) of the place. These include the Swamp Wallabies, the Goannas, the Bandicoots, Echidna and many varieties of bird and plant life. Finally, there would be a training session on how to use the land management equipment that NPWS was so generous in sharing.

Third, in our planning framework, we needed to have prepping sessions to get the site into a condition that could safely be burnt. Prior to colonisation, Walumada was cared for seasonally by the Walumadagal, and cultural fire practice was critical for the wellbeing of the landscape. Without cool fire, mega-fires destroy the soils, the plants, the trees, the flora and fauna. Without these presences, human beings cannot survive. For thousands of years, across the continent now called ‘Australia’, cultural relationality with Ngurra has been undertaken through fire and other practices for sustainable futures. As Australian Indigenous peoples maintain the longest continuous culture on the planet, I feel that our cultural practices are the very definition of ‘sustainability’ (Ngurra et al., 2019). Today, however, because of the disruption of colonisation across 236 years, the condition of Ngurra has not been maintained, especially in urban areas, and so, preparation of the vicinity for the burn was a critical step. Additionally, by having the prepping sessions, we opened an opportunity to bring our allies into the circle. While Dharug women led the journey, our allies contributed their skill sets, and reciprocally, we could educate them in the art of sustainable relationality, with Ngurra.

In undertaking these three phases, we organised a budget so that participating Dharug women could be paid for their time and expertise, as well as providing sufficient funding for camping, firewood, and other necessary equipment. This included a Dharug-owned camping kitchen trailer, and a water-truck, which belonged to members of YBG, and is often in use at Shaw’s Creek, all of which assisted in the preparations. Additionally, while the activisms at the waterhole were part of the DPE project, I felt it important to have BWH Stakeholder Days along the way, to grow our ally numbers, and keep stakeholders informed, as part of my MUFIR project.

‘Burning Love’: Building Relationality

The first BWH Stakeholders Day was on May 26th, 2022 (Figure 1). Its purpose was to inform invested local groups of what we were proposing to do. Along with various interested Dharug women, we had representations from the three Councils whose boundaries meet at the BWH. They include Hornsby, Kuri-Ngai and Ryde Councils. Additionally, NPWS rangers and fire managers, Friends of the Lane Cove National Park (FLCNP), and Australian Association of Bush Carers (AABR) were present. Other support was provided from departments in Macquarie University, including: Critical Indigenous Studies; Environmental Sciences; Media, Communications, Creative Arts, Language and Literature (MCCALL); and a Faculty of Arts Early Career Research grant assisted with funding. Finally, VC’s (DPE) participation was much appreciated as well. The event involved a walk down to the waterhole from campus, including bushcare ally Janet, who is part of AABR and FLCNP. NPWS provided rangers to assist in making sure the group was safely guided. Mark Parry, of Parryville Media, covered the footage and photography for the day. We returned from the top of the valley back to campus by bus, had lunch and then Corie and I did a workshop in the afternoon, outlining what we were hoping to achieve. Attendees numbered around 30. While we had discussed doing the women’s camp and prepping later in 2022 the poor weather delayed the camp until 2023.

Instead, a second Stakeholders event was held in December 2022, to keep everyone in touch and outline our plans for 2023 (Figure 2).

Making History 1: Dharug Women Camping on Walumada

Almost exactly a year after the first Stakeholders Day, between 19-21st May 2023, Dharug women gathered and camped on Walumada, having gained unprecedented permission from Ryde Council to undertake this historic journey (Figure 3; Figure 4). No Aboriginal people had been allowed to ever camp in Ryde since the earliest colonial period, and no one had ever been permitted to camp in that park since local government existed.

Making history together were six Dharug women, two Dharug men, and seven allies, totalling 14 participants. These campers included:

-

Dharug Women: Jo, Corie, Venessa-Possum, Be, Rosey, and Leisa.

-

Dharug Men: Shannon and Tim (Camp Managers)

-

Allies:

- Lane Cove National Park Field Officers: Robyn, Tegan, and Josh.

- MQU: Sandie and Marnie

- Videographer: Mark Parry, Parryville Media.

The Women’s Camp was to be the forerunner to the cultural burn that was planned for the second half of 2023. Once again, weather conditions were poor and so the prepping of the site ready for the burn was pushed back until 6th-9th March, 2024. In the meantime, on 1st February 2024, we held our third Stakeholders Morning (Figure 5).

This third event was to bring together those who were continuing to walk with us as we began the third year of our journey. While the numbers weren’t as large as at previous events, nevertheless, those who did attend we knew would join in for the actual preparations of the site ready for the burn. These took place little over one month later, between 6th and 9th March, 2024 (Figure 6).

Prepping workshops 6th-9th March, 2024

Rather than camping this time, Dharug women stayed in accommodation nearby. Participants in the preliminary preparations of the site included six Dharug women (Corie, Venessa-Possum, Leanne, Rosey, Leisa and Jo), 2 Dharug men (Lex, Shannan), and 18 allies, making a total of 26 participants. These numbers indicate that there is solid support from our allies and community who are interested in being a part of our journey.

Based on the interviews held with some of the attendees at the end of the three days, some of the human outcomes included:

- Deeper bonding with the place called ‘Brown’s Waterhole’ by allies and Dharug community.

- Deeper bonding between Dharug women as they share time and storying

- Greater recognition of the importance of caring for Ngurra in an urban environment

- Better understanding of the practice and place of using ceremonial guwiyang and smoking as a starting point for healing Ngurra and people as a contrast to Western fire practices.

- Increased respect by allies for Dharug women’s approaches to guwiyang as a nurturing activity

- More understanding of Ngurra and how caring for Country enables Country to provide beneficial outcomes for people. Examples of this from the site included provision of materials for artworks, such as Bamuru (Lomandra longifolia) for weaving, Dybung/Mambara (Persoonia sp.) bark for medicine, and wombat berries (Eustrephus latifolia) as fruits,

- The wonderful work by Dharug artist, Leanne Tobin, produced the painting, ‘Dharug Women’s Cultural Burn on Wallumadagal Ngurra, 2024’ (Figure 7).

As can be seen from the journey outline above, Aboriginal cultural, cool-fire burns when enacted in the city are so much more than just lighting a match. They involve building relationality between humans, as well as with other-than-humans. As such, deepening relationality with the presences, places and people becomes an act of ‘Burning Love’, by connecting, and caring. In the process, we grow our belonging to them.

The next phase of this paper now turns to the work undertaken to better understand the impact of cool-fire, cultural burning on the biodiversity of that place in Walumedegal Ngurrang. Doctoral candidate and ally, Gabby, and her supervisor Em, provide details below on cultural guwiyang and its impacts on biodiversity, based on the Brown’s Waterhole activation.

PART 2

CULTURAL GUWIYANG AND BIODIVERSITY

Gabrielle Brennan and Emilie Ens

The growing risk of bushfire in Australia, especially in highly urbanised contexts, presents unprecedented and unknown destructive threats to Ngurra, including the biophysical ‘other-than-human’, as well as people and infrastructure (Dickman, 2021; Norman et al., 2021). Furthermore, recent catastrophic bushfire events have highlighted the potential of Indigenous cultural burning practices as a management tool and as a remedy to looming climate crises (Robinson et al., 2021). However, for this to be effective, dominant Western systems must shift towards increased engagement and collaboration with Indigenous peoples (M.-S. Fletcher, Romano, et al., 2021), to co-develop culturally informed and Indigenous-led solutions for fire management (Bourke et al., 2020; Ens et al., 2015). Indigenous groups are increasingly interested in working with non-Indigenous allies in cross-cultural contexts, to bring together Indigenous and Western knowledge systems and approaches (Ens et al., 2015). It is within this context that we were invited, as non-Indigenous researchers and allies, to collaborate with Dharug women to co-develop and conduct cross-cultural monitoring of the April 2024 cultural burn led by the DWACFA (Dharug Women and Allies Cultural Fire Alliance).

Walking together: Start of the collaborative research journey

This collaborative research and cross-cultural monitoring journey involved Dharug women and Em (a non-Indigenous ecologist) initially working together to co-develop a biocultural monitoring App using CyberTracker software, for Brown’s Waterhole. Biocultural monitoring combines monitoring of biological and cultural values through multidisciplinary approaches and often incorporates Indigenous and Western epistemologies (DeRoy & Darimont, 2019; Ens et al., 2015). Em and Gabby (a non-Indigenous PhD student ecologist) offered to assist Dharug women with more biocultural research. As non-Indigenous female allies, we had a strong interest in working with Dharug, the Traditional Owners of Walumada, where Macquarie University is located, while aligning Gabby’s doctoral project with the cultural burn. The aim of this collaboration was to co-develop cross-cultural monitoring approaches to assess outcomes of local cultural burning efforts. There is limited research on the outcomes of cultural burning, despite increasing interest (see Cavanagh, 2022; McKemey et al., 2022) and we would draw on our previous experiences in cross-cultural ecology and fire management in the Northern Territory and southern states. Given the inner-urban context for this burn compared to other cultural burns that were taking place in less densely populated areas of Sydney, this collaboration provided a unique opportunity to showcase the benefits of cultural burning within inner-urban landscapes.

From initial yarning sessions with the DWACFA, the women expressed interest in understanding the effects of the Dharug cultural burn at Brown’s Waterhole through an ‘other-than-humans’ lens. Specifically, they were interested in understanding how culturally important Dharug plants, fauna and soil responded to Dharug guwiyang (fire). With these Dharug-led questions as our focal point, we co-developed approaches and ways that we could further understand the interactions and responses of ‘other-than humans’ to guwiyang. This work would build on previous biocultural monitoring undertaken by the Dharug women and Em, who had mapped out key Dharug plants and associated women’s knowledge, alongside use of three wildlife cameras at Brown’s Waterhole. We conducted further research using systematic, spatially and temporally replicated monitoring of culturally important plants, wildlife and soil responses to cultural burning. Trips down to Brown’s Waterhole with Dharug women helped gain an understanding of the intended burn area (size, slope, fuel load, aspect) and key Dharug goals for the burn, which included reducing the extent of dominant species, Daynya (Common hop bush, Dodonaea triquetra) and Gurgi (Bracken fern, Pteridium esculentum), to promote valued species like Bamuru (weaving grasses like Spiny-headed Mat-rush, Lomandra longifolia; Pithy Sword-sedge, Lepidosperma laterale), Dybung/Mambara (Broad-leaved Geebung, Persoonia levis; Narrow-leaved Geebung*, Persoonia linearis*) and Gulgadya (Grass Tree, Xanthorrhoea media). Another key outcome was to care for local fauna residents through low impact burning. These trips also revealed the presence of the distinct Burraga diggings (Long-nosed bandicoot*, Perameles nasuta*), which triggered interest in undertaking further fauna monitoring using more camera traps, given that they had not previously been recorded through preliminary camera traps set up by the women at Brown’s Waterhole. There was also an interest in understanding the responses of soil at Brown’s Waterhole to the cultural burn, given that soil properties can change after fire, such as pH (acid-alkaline), electrical conductivity (a measure of salts), soil moisture and carbon content (Country et al., 2024; Noble et al., 1995; Teixeira et al., 2022). During the initial relationship building and project scoping period, we also co-developed a Dharug cross-cultural field guide to culturally important plants and animals at Brown’s Waterhole. The guide included Dharug women’s knowledge of different species, known Dharug names, biological and ecological knowledge (descriptions, resource and habitat needs, reproductive information) and known Indigenous uses. This field guide aimed to bring together the different knowledge bases and serve as a tool for species identification and knowledge building.

The scientific basis of the biocultural monitoring adopted the Before-After, Control-Impact design (BACI) (Underwood, 1994), informed by similar studies on the northern tablelands of NSW by the Banbai rangers (McKemey et al., 2019). Our BACI design involved measuring parameters before and after the cultural burn at Brown’s Waterhole, compared to three control sites that were not burnt. The non-burn sites were chosen for similar habitat qualities (e.g., similar flora species, aspect, slope, area), and all were in Lane Cove National Park (Figure 8). This would allow inferences about the responses of the ‘other-than-human’ at Brown’s Waterhole following the cultural burn and elimination of other potential explanations, such as rainfall, seasonal responses and site differences.

Given that the women’s target burn site at Brown’s Waterhole was a relatively small area (60m x 50m), aligned with their intention to target the Daynya and Gurgi, this influenced decisions about the structure and layout of the monitoring scheme. The site transitioned from drier uphill to wetter downhill areas closer to Terry’s Creek, which the Dharug women said would be less likely to burn due to the vegetation and leaf litter being damper and less likely to catch fire.

Relationality through Cultural Burn Workshops

As part of this collaborative journey with the Dharug women, we were invited to the workshops down at Brown’s Waterhole throughout 2024. This included participating in the pre-burn workshop in March 2024, which was an opportunity to meet other Dharug women who were a part of the DWACFA and share stories of the biocultural monitoring. We intended to complement the Dharug women’s cultural considerations with quantitative biocultural assessments. The pre-burn workshops provided an opportunity to interview some of the women about how they thought Brown’s Waterhole would change after guwiyang and what responses they hoped to see for the ‘other-than-humans’. This allowed deeper understanding of the Dharug women’s perspectives, values, aspirations and knowledges, in both the biophysical and cultural sense. As researchers and non-Indigenous allies, these workshops were an important process in connecting, learning, building relationships and fostering trust, reciprocity and a shared understanding about how we could work together to build evidence of the benefits of cultural burning in urban landscapes.

These experiences helped to broaden our perspectives beyond our Western scientific monitoring lens, as we learnt about the relationality of Ngurra, kin, human and the other-than-human residents through the eyes of Dharug women. They offered a counterbalance to the narrowness of quantifiable parameters and statistics that are central tenets of the ‘dominant’ Western scientific method, as we listened to the women talk about the importance of the cultural burn, and how it was a healing restorative process for Dharug women’s culture and spirit. The cultural burn and workshops were a chance to participate and observe, witnessing the reignition of Dharug practices in a contemporary inner-urban setting.

When we started to burn Ngurra, the women started at the top of the site, with all of us in a line, striking multiple ignition points, creating mosaic patches or circles (Figure 9). Guwiyang moved very slowly at first, given that it was still quite moist, it was earlier in the day, and there was low wind. Participants observed that the bracken ferns were especially slow to catch fire and required a bit of encouragement, such as by adding dried Gulgadya leaves. As the day progressed, the Dharug women and allies moved across the site, working in groups and lighting multiple ignition points, encouraging the ignited fire circles/patches towards each other (Figure 9). Guwiyang trickled slowly and became quicker later in the day, when it was hotter and there was direct sunlight on the site. We used rake hoes to create containment lines when there was too much fuel, as a way of controlling any guwiyang that might spread too quickly or burn too intensely (Figure 9). However, there was never a sense that the fire was ‘out of control’. This was also reflected through comments made by the National Parks rangers attending and participating in the cultural burn, with multiple individuals noting that this type of burning was much slower and cooler than prescribed burns they had conducted.

After the burn

Following the burn, we repeated the biocultural monitoring to get a sense of how the fauna, target flora and soil responded. Immediately after, we collected soil samples from Brown’s Waterhole and the control sites and set the camera traps back up to see what animals might be returning to the site. A couple of months later (July 2024), we followed up with some post-burn habitat and vegetation assessments, looking for any change in vegetation, including how bracken and Daynya had responded, and to see if any species of interest were emerging.

Jo and Gabby returned to the site and walked around making observations and Gabby then interviewed Jo about how Ngurra was responding to guwiyang. Jo’s observations of the burn included: lots of fungi emerging after the fire, small grasses and new Gurgi fronds emerging, as well as Gulgadya seedling emerging in areas that were burnt (Figure 10). This aligned with Dharug women’s knowledge about bushtucker and other culturally important plants returning after guwiyang from seedbanks under the ground. Jo noted that the area had been cleaned of the dominant Daynya, making way for other plant species to emerge in their place. Observations immediately before the burn compared to five months after were that fresh Gurgi fronds were re-emerging, whilst Daynya had not returned (Figure 11). This was evident from photos captured during habitat surveys before and three months after the Dharug cultural burn, showing a ‘cleaning out’ of dominant Daynya and Gurgi (Figure 12). Gabby also shared observations of other adult culturally important plants, such as Dybung/Mambara and Guman (Forest oak, Allocasuarina torulosa), that did not appear to be negatively impacted by guwiyang, with only mild scorching to low hanging leaves.

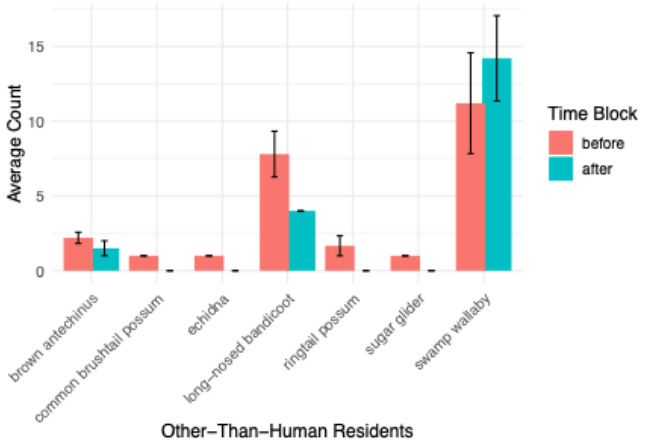

Wildlife cameras detected many local fauna residents and provided some insights into animal activity before and after the Dharug cultural burn (Figure 13). Species caught on camera at Brown’s Waterhole included: Burraga, Bagarayi (Swamp wallaby; Wallabia bicolor), Barrugin (Short-beaked echidna, Tachyglossus aculeatus), Burumin (Common brushtail possum; Trichosurus vulpecula), Wali (Common ringtail possum; Pseudocheirus peregrines), Dyubi (Sugar glider, Petaurus breviceps), Bidyiwung (Eastern water dragon, Intellagama lesueurii) and the brown antechinus (Antechinus stuartii).

Burraga showed a drop-in activity at Brown’s Waterhole after the fire, potentially due to a decrease in vegetation cover, as well as sensitivities to disturbance (Figure 13; Brennan et al., 2025), as research in other parts of south-east Australia have also shown (Arthur et al., 2012; Claridge & Barry, 2000). Other research suggests that Burraga benefit from having patches of unburnt vegetation when there is fire (MacGregor et al., 2013). A couple of months after burning our cameras showed reemerging Burraga activity around Brown’s Waterhole. Bagarayi showed a slight increase in activity following the fire (Figure 6; Brennan et al., 2025), which may have been due to increase in food sources, such as new green grass shoots and fungi, which the cameras showed the wallaby eating post-burn (Figure 14).

‘Burning Love’ Learnings

Through this collaborative journey with the Dharug women, we have gained some invaluable insights and learnings, both as researchers and human beings. The process challenged our dominant Western scientific mindset by broadening our capacity to see, listen, hear and experience Ngurra through a more expanded and considered lens. This process of working together through principles of relationality, transparency and reciprocity helped to breath meaning and purpose into the cross-cultural monitoring and created, consolidating feelings of a shared learning journey. Being invited to visit and engage with Ngurra and the women at different stages was an immense privilege, as we learnt about the importance of reigniting culture and practice, in an urban context, to heal both Ngurra and people.

PART 3

Guwiyang (Fire)

Cultural Burning and the Reconnection to Country

Corina Norman and Rosemary Norman–Hill

Introduction

Cultural burning, also known as Indigenous fire management and firesticks, is a practice deeply rooted in Wagulgu Yiyura (First Peoples) knowledge systems worldwide. Wagulgu Yiyura have used fire for millennia to manage landscapes, foster biodiversity, and maintain ecological balance carefully. A time-honoured tradition, which involves intentionally applying fire to nurture Ngurra, promoting the health of the land and its inhabitants.

The burn days at Browns Waterhole, held from 24-28 April, 2024, was a women’s led burn supported by the Dharug community, along with NSW Department of Planning and Environment (DPE), National Parks and Wildlife Services, (NPWS), Royal Fire Service (RFS), Macquarie University and residents from all walks of life, who arrived at the site with a shared purpose. From the outset, it was clear that this was more than a practical exercise. It was a ceremonial act of reciprocity and care; a contemporary example of traditional cultural burning weaved in as a powerful tool for reconnecting with Ngurra. An act of ‘Burning Love’.

Good Intent

Each burn day began with a smoking ceremony (Figure 15).

A gathering steeped in tradition and deep respect for Ngurra with the principles and values of Yanama Budyari Gumada (To Walk with Good Spirit), as shared by Uncle Lex.

Participants embraced patience, humility, and respect, bringing us into a shared presence, focused, and grounded.

The air was filled with the scent of burning eucalypt leaves, mingling with the murmurs of songs acknowledging the ancestors and seeking their guidance. These opening moments set the tone for a journey that was both deeply personal and profoundly communal. These intergenerational gatherings, with members of the Dharug community sharing stories, framed the burn within the cycle of life, death, and renewal.

Those in attendance, many of whom were engaging in cultural burning for the first time, listened intently, their presence a testament to the continuity of knowledge and cultural resilience. Along with the adults, there were gurung (children), wide-eyed and curious, absorbing the significance of the practice as future custodians of this tradition.

As the smoke curled through the trees and danced across the ground, it prepared us spiritually and called upon Bimal Wayanga (Mother Earth) and Burra Biyanga (Father Sky) to join us in this dialogue.

Infusing Language and Ceremony as 'Burning Love

Dharug Dhalang (language) infused the entire process, reconnecting Ngurra to her ancestral sounds. Language was a bridge between generations and species, weaving a symphony of voices that celebrated renewal. The intertwining of human words with the natural sounds of Ngurra created a profound resonance, reaffirming the inseparable bond between Yiyura (People) and Ngurra.

Through our ceremonial songs/chants, dances, and yarning circles, Ngurra, our home and Country, heard her Dhalang (language) being spoken again. The rhythmic flow of our words brought life to the spaces we walked, echoing through the yarra (trees) and across the badhu nuru (waterhole). This was more than communication. It was a rekindling of an ancient connection, a healing of songs sung back to Ngurra.

The brother and sister creatures like the Bidyiwung (Edgy Eddy the Eastern Water Dragon), Bagarayi (Swamp Wallaby), Girrawi (Sulpha Crested Cockatoo), and Wirriga (Lace Monitor) moved through this space with curiosity and purpose, as if responding to the familiar cadence of the Dharug words (Figure 16). The rustling of feathers, the chirping of the birds, the soft padding of paws, interwoven with ours, creating a symphony of voices that celebrated this act of renewal.

It felt as though Ngurra, and her inhabitants were not merely witnesses but active participants in the ceremony, hearing and responding to the revival of the Dharug Dhalang and cultural practices. As we spoke to our living landscape with the animals, birds, insects, trees, grasses, medicine and food plants, we informed them of the guwiyang (fire) to come. It was a reminder of the reciprocal relationship we share with Bimal Wayanga (Mother Earth).

The dhalang we used was not just our language but also that of Ngurra, Badhu (water), and our brother-sister creatures. They received it with a knowing that transcended time. Hearing their language and ours together affirmed that we were not separate from this place but intricately connected to its rhythms and cycles.

It was not just the guwiyang that renewed Ngurra it was also the dhalang, the Bayala (stories), Baraya (singing of the songs) and the acts of linguistic care that spoke directly to the bindhi (gut feeling) and the budbud (heart) of Ngurra.

Through Dharug dhalang, we were reminded that Ngurra listens and responds and that our words have the power to heal and connect across generations and with other-than-humans alike.

Commitment of Ceremony: Painting up and Signing into Country

At Brown’s Waterhole, two distinct, yet connected cultural protocols guided our engagement with Ngurra, each carrying deep meaning and cultural responsibility. Participants first painted up with ochre, as an integral part of the smoking ceremony, an act of unity, of spiritual connection and cultural identity, led by the Dharug women. This ceremonial act helped us to become present, respectful and ready, clearing away anything that we didn’t want to carry into the work ahead. The ochre, carefully applied to the skin, marked our bodies of the story of where we were, who we came from and the intention we brought to Ngurra. The smoke drifted across our skin and spirit, clearing a path, removing what was heavy or unhelpful, so that all could enter with clarity, reminding us to come clean, to listen deeply and walk gently.

The second, and equally sacred, act was signing into Country (Figure 17). This practice, guided by Uncle Lex, involved using pre-mixed ochre and water, placing it into one’s mouth, and gently blowing it onto a yarra (tree) or nearby giba ganya (rock shelter) on the site. This was not a symbolic gesture alone. It was a binding act, a physical and spiritual commitment to care for that place. In signing in, participants made a promise to Ngurra, to our Ancestors, and to all present: that they were there not just in body, but in spirit and intent. This vow will linger beyond the ceremony, etched into Ngurra itself. Once you sign in, you do not forget. You become accountable to that place, through a relationship of ongoing care and reciprocity.

Reflections on the Burn Days

Day 1 - Preparation and Connection

The burn began with a series of smoking ceremonies, centring all participants on the principles of Yanama Budyari Gumada through patience, humility, and respect. This act cleansed the space on Ngurra, for the journey ahead. Preparation involved cultural and ecological assessments of the site, where we spoke to the grasses, trees, and brother and sister creatures, informing them of the guwiyang to come and seeking their permission. Practical tasks such as boundary marking and assessing wind directions were infused with spiritual alignment to Ngurra’s rhythms. This dialogue with Country highlighted our interconnectedness and reinforced that guwiyang would proceed only with consent.

Day 2 - Lighting the First Flame

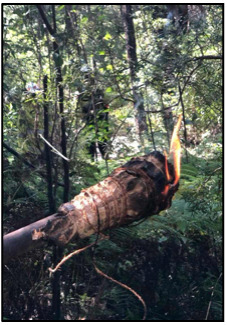

The first flame with our Dyarraba (Firestick) was lit with intention and respect. The guwiyang, imbued with the teachings of cultural burning, moved slowly and deliberately, consuming dead and decaying matter and stimulating growth, cleansing Ngurra without destruction. Several Dyarraba were made as ceremonial tools and used to light small fires at designated points (Figure 18). Carefully monitored, these fires were the starting points for the controlled burn. Watching the flames take hold, we felt a profound connection to past ancestors who had performed similar ceremonies on this Ngurra for thousands of years.

The crafting of our Dyarraba originated from a memorable experience in 2018, during a Cultural Burn at Shaw’s Creek. Pairrebeenne Trawlwoolway woman, Lauren, brought along a Dyarraba crafted by her uncle, which was used to light our women’s ceremonial fire at Shaw’s Creek Aboriginal Place (Figure 19). With this vision in mind with cultural protocols and permissions granted, Corie and Uncle Lex created the Dyarraba for this burn, using stringybark, paperbark and other materials sourced from the bush. Their skill and care brought these Dyarraba to life, honouring the cultural practice and the inspiration sparked by Uncle’s creation.

Observing the Burn

As the guwiyang moved through the underbrush, it revealed layers of the ecosystem that had been hidden. The smoke rose in spirals, carrying our intentions skyward. We moved alongside the flames, using our tools to guide the fire and ensure it stayed within our natural fire breaks. The sound of crackling vegetation was rhythmic, almost like a heartbeat.

The heat of the guwiyang activated dormant seeds within the soil. Grass trees, which had been prepared by nature for this moment, began to release their seeds. The burn also cleared away invasive species, providing space for native plants to regenerate. All the while watched intently by our feathered friends who seemed to instinctively know they were not in danger.

At the same time, we took care to protect areas of cultural significance, ensuring that guwiyang did not touch certain rocks or trees imbued with spiritual meaning.

Day 3 - The Fire’s Dance

By the third day, the fire’s path revealed Ngurra and her resilience. It took only what was necessary, leaving space for regeneration. Walking the charred ground, all involved shared stories of balance and responsibility, emphasizing the role of cultural burning in maintaining harmony with Ngurra. The fire’s journey was a visual reminder of the delicate relationship between Yiyura (people) and Ngurra. Each step we took on the blackened soil, reinforced our role as caretakers, not owners of Ngurra.

Day 4 - Healing and Renewal

The fourth day brought healing to Ngurra Yiyura (Country and People). The fire cleared invasive species from the space creating room for potential native plants to thrive. Seeds dormant beneath the soil stirring with the promise of new growth.

Our healing circles allowed participants to reflect on personal and communal transformations. Stories of renewal paralleled the cycles of life and death intrinsic to cultural burning. Art and song expressed this healing, blending traditional rhythms with contemporary influences to ensure the stories of the burn endure.

Day 5 - Closing Ceremony

The final day was one of gratitude and closure. A ceremony marked the completion of the burn, with offerings made to Ngurra, Warunggad Gumada (Old People and their spirits) including Yiyura. The smoke from the sacred smoking ceremony carried blessings into the air, closing the journey with reverence. We were all reminded through the experience that cultural burning is not a single act but an ongoing relationship with Ngurra.

Each day at Brown’s Waterhole demonstrated the transformative power of guwiyang guided by cultural protocols. By burning in small, deliberate sections, we nurtured growth, regenerated Ngurra and protected it from the devastation of unrestrained wildfires. Everyone left the site with a renewed sense of responsibility and belonging, carrying forward lessons of cultural resilience and ecological stewardship.

In recreating our cultural practices, we cannot forget that since colonisation, the ceremony of burning Ngurra has been disrupted. The European invasion of Australia in 1788, bringing with it scientific and Western knowledges has since been prioritised within environmental management and formal Australian education, at the expense of recognition and respect for Indigenous presences, practices and knowledges (Ngurra et al., 2021). The suppression of our traditional methods, compounded by the violent dispossession of our Yiyura from our Ngurra (Norman-Hill, 2020), has left many landscapes unmanaged and vulnerable.

Ngurra has suffered. Its health visibly declining, as evidenced by the catastrophic bushfires which are increasing in intensity and frequency. Guwiyang, once a tool of renewal, has become a force of destruction in the absence of this ancestral wisdom. Despite this, we have witnessed a resurgence of cultural burning, which is not a revival of a lost tradition, it was never lost, but a reawakening for those now willing to listen.

Land management agencies and conservation groups are beginning to understand the vital role of Wagulgu Yiyura (First Peoples) knowledge in caring for Ngurra. Across Dharug Ngurra and beyond, partnerships are being formed, and the guwiyang are being lit again in ways that honour both Ngurra and its Yiyura.

As we face the challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss, it is vital to return to these ancient practices. Cultural burning holds lessons not only for Ngurra but for how we walk together on it. It reminds us of the delicate balance required to sustain life and of the responsibilities we share to protect Ngurra for future generations.

Guwiyangu Summary

The Brown’s Waterhole cultural burn is a testament to the enduring relationship between people and Country. By integrating fire, language, and ceremony, we honoured ancestral wisdom, ancestral spirits, and our living landscape, fostering renewal and healing. This practice is rooted in the rhythms and cycles of the natural world, guided by knowledge passed down through the voices and hands of our old ones.

As Uncle Lex always reminds us, Yanama Budyari Gumada (to walk with good spirit) is essential to move through the world with patience, humility, and respect, always guided by the good work we are called to do. It is about reading the signs of Ngurra, knowing when the soil is ready, when the plants signal their need, and when the weather will carry the fire gently across the landscape. Dharug and other Wagulgu Yiyura have understood these relationships for millennia, creating a patchwork of habitats that support biodiversity and strengthen ecosystems. The ceremonial act of the cultural burn was rooted in the principle of Yanama Budyari Gumada, ensuring that every action was deliberate, respectful, and aligned with the rhythms of Ngurra. It marked a renewal of cultural practices, a commitment to healing, to Country and to a stronger future for generations to come.

Cultural burning is far more than a land management tool. It is a practice that embodies the wisdom, resilience, and survival of Dharug and other Wagulgu Yiyura (First Peoples). As the Wagulgu Yiyura Dharug Ngurragu (First Peoples and Custodians of Dharug Country), we hold knowledge that can guide us through the challenges of today and tomorrow. Working together, with guwiyang and Ngurra as our teacher, we can restore balance, ensuring a vibrant future for all who call this place home.

Conclusion and Moving Forward

This paper has brought together different perspectives and voices that together formed the journey towards, and enactment of, the first ever Government-invited Dharug women’s-led cultural burn since colonisation. As outlined in this paper, this journey was centred in the cultural understanding that caring for Ngurra through fire is an act of ‘burning love’: an act of caring for kin, for other-than-humans, and for other humans, as we proceed to address the real threat that is facing us through human-induced climate-change. Ultimately, this act of burning love is not a borrowed metaphor, but a truth we live. It speaks of intimacy with Ngurra, where acts of care are grounded in Country and of a fire that does not destroy but connects. Enabling this kind of fire to carry us forward benefits all sentient beings. In so doing, we have witnessed a resurgence of cultural burning, which is not a revival of a lost tradition, it was never lost, but a reawakening for those now willing to listen.

Together we have brought together three narratives: a procedural account over time, a Western scientific approach to engaging with a cultural burn, and finally, a Dharug cultural account of why, and how this successful women’s-led burn, and the process surrounding it, is so important as we walk from the colonial trauma of the past, into the present, for the future.

Now in 2025, MQU has established the Australian Harmony Centre for Ecosystem Futures (AHCEF), a recognition of the importance of caring for Country in the city and enabling the continuity of Dharug women’s-led cultural burning in association with the catchment group allies along the Durumbura Dhurabang valley.

Step by step, by returning the river to the centre of this localised activism we can focus on the wellbeing of Ngurra as integral for the benefit of human and other-than-human beings within an inner-urban environment. As such, building relationality across government and other jurisdictions, bringing together the neighbours of the river with Dharug Aboriginal community and including their approaches to caring for Ngurra, recognises and reinforces the universal truth that underpins the saying: “Healthy Country, Healthy People”. For sustainable futures, it is absolutely critical that we walk together, to mitigate increasing climatic catastrophes.

Yanladyi budyari gumadawa

Walking together in Good Spirit.

__controlling_and_bringing_together_.png)

__gulgadya_seedling_emerging_in_areas_that_wer.png)

_and_5_months_after_guwiyang__septembe.png)

_and_three_month.png)

__bagarayi_ea.png)

__controlling_and_bringing_together_.png)

__gulgadya_seedling_emerging_in_areas_that_wer.png)

_and_5_months_after_guwiyang__septembe.png)

_and_three_month.png)

__bagarayi_ea.png)