Introduction - Communication, storying and research in an Indigenous space

“In the strange ways that colonialism works, […] we constantly find ourselves living inside someone else’s story.” (Smith, 2020, p. 366)

Communication is a dynamic field encompassing a range of approaches that can explore, critique, and transform how messages are created, shared, and understood. At its core, communication is not just about transmitting information but about shaping meaning, identity, and action within social and cultural contexts. Approaches to communication vary widely but can essentially function as sites that evoke questions of power, inclusion, and the impact of narratives on individuals and communities (Carragee & Frey, 2016). Traditional communication approaches often emphasise clarity, persuasion, and universal messaging but can overlook cultural and systemic influences on how messages are received (Cissna et al., 2009; Dutta, 2022). In contrast, social justice communication, engaged scholarship, and communication activism seek to confront oppression and promote equity through storytelling, community collaboration, and systemic intervention (Carragee & Frey, 2016; Frey et al., 2020). Applied and critical cultural communication further explore how power dynamics marginalise voices and shape meaning-making (Barge, 2023). Decolonial approaches challenge Western-centric paradigms by centring Indigenous knowledge and place-based perspectives, advocating for communication strategies that honour cultural specificity and lived experience (Na’puti & Cruz, 2022). Overall, communication can play a transformative role in dismantling systemic barriers, amplifying diverse voices, and reshaping dominant narratives.

The power to communicate is thereby inextricable from the social/political power structures and systems that shape stories. In Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa), as in many other places where Indigenous lands have been colonised, the dominance of Western cultural norms - presented by colonial systems as universally applicable - have dominated our everyday stories. With the annexation of Aotearoa by Great Britain in 1840, the voices that embodied Māori (Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa) values, traditions, worldviews and stories became alienated alongside the extensive alienation of lands and home spaces (Boulton et al., 2022). Colonial narratives justified land theft and marginalisation, eroding Māori authority, Māori language and denying Māori worldviews (Pihama, 2022).

Research: Whose story is it anyway?

“[…] cultural others speak but we may be unable to hear them because we cannot read alternative and culturally relevant ways of exerting voice that differ […]” (Na’puti & Cruz, 2022, p. 7)

Research, or the act of obtaining data for the purpose of exploration or answering specific questions, is a way of generating stories. For a long time, Western research practices positioned Indigenous peoples as the objects to be studied, within Eurocentric, colonial frameworks which dominated the ideological and structural paradigms of knowledge-creation (Boulton, 2020). These approaches embody their colonial legacy, consequently favouring Western methodologies and knowledge over Indigenous values and practices (Kukutai et al., 2021).

The legacy of extracting “data”[1] has created a deeply entrenched suspicion of research within Indigenous communities, including Māori communities of Aotearoa (Smith, 2021). For Māori, the ongoing struggle lies in presenting narratives that accurately reflect our lived experiences and the impacts of colonisation in Aotearoa. Such narratives challenge the assumptions, norms, and practices of knowledge gathering, interpretation, and dissemination within Western academia by expressing sovereignty through re-narrating aspects of research production (Smith, 2021). Indigenous methods-continue to evolve to “help scholars imagine communicative possibilities that might exist” (Na’puti & Cruz, 2022, p. x).

‘Kaupapa Māori research’ is an approach that is driven by Māori worldviews, values, and practices and targets power imbalances in research to foster Māori aspirations (Smith, 2021). ‘Kaupapa Māori’ is the Indigenous naming of a worldview, an aspiration and an approach that grew out of the need to transcend the cultural erasure of Māori knowledge and experience and which enshrines Māori “sovereignty, the value of treasures passed down from our ancestors, and acknowledgement of the importance of whānau [family] as the building block of Māori society” (Cram et al., 2023, p. 54). Kaupapa Māori thereby is a vehicle that is a ‘stake in the ground’ for our own Māori ontology - worldviews - and epistemology: our ways of knowing.

As part of the Kaupapa Māori evolution, how research is communicated and to whom, has become increasingly important, particularly given that - despite years of research activity about Māori - the disconnect between research findings and meaningful improvements in outcomes for Māori remains a substantial issue (Allport et al., 2023). The ‘stories’ told about Māori within the dominant discourse of Aotearoa are those of lack, disparity and limitation; where the building of this country as a nation itself is a story about “a site of power imbalance, where Māori histories tend to be reduced to myths and pre-history as decoration to the central story” (Mahuika, 2009, p. 134). Deficit stories about Māori have never left the dominant communication discourse and can be found daily within the media, political propaganda, and the rationale behind the governing systems of Aotearoa (Barnes et al., 2012).

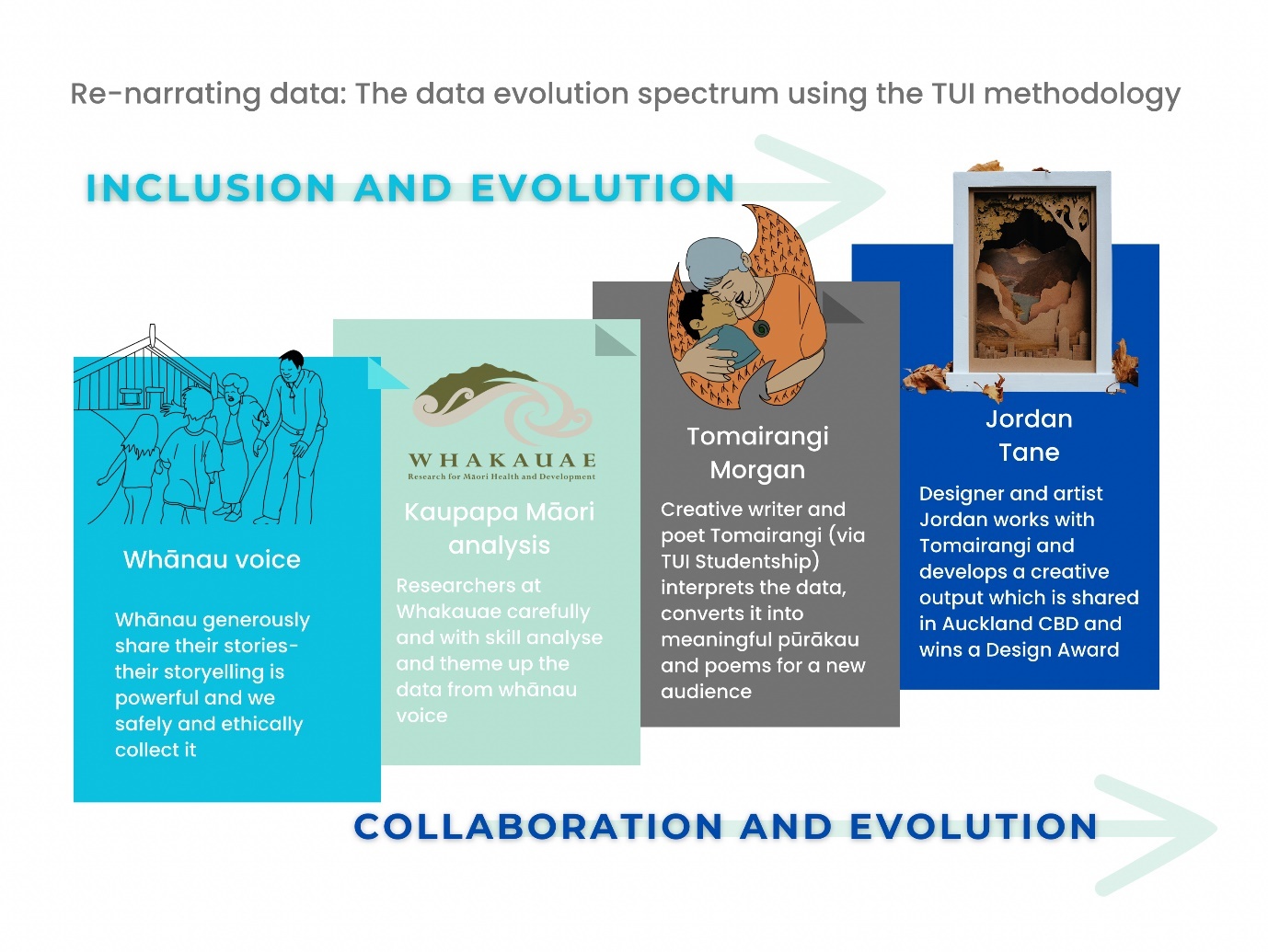

As Kaupapa Māori researchers we - the authors - know that the way in which we shape and communicate research determines whom the story belongs to, who needs to tell it, and who needs to hear it. While Indigenous peoples, particularly in the Pacific, possess their own rich, non-Western research methods that are grounded in relational knowledge systems, cultural protocols, and community-based ways of knowing, within a colonial context, our stories are typically ‘othered’ as they contrast against dominant narratives and communication processes. To ensure our particular researcher group is able to highlight Indigenous narratives, we have developed a bespoke methodology which addresses Translation, Uptake and Impact of research (TUI[2]). TUI is a dissemination strategy developed by Whakauae Research Services Ltd, an independent Iwi owned research centre in Aotearoa who report to their Iwi owners Ngāti Hauiti (a tribal community from the Rangitīkei in the North Island). The TUI model is based on our research values, aims and worldviews, and responds in direct relationality to the needs of the Māori communities that we work for (Allport et al., 2023).

The TUI approach is also a way to self-reflect on deeply ingrained colonial methods of knowledge production and dissemination in the academy, where cultural essentialism and ownership over the research “data” and ‘findings’, can be de-constructed and challenged as part of the process. One of the notions that has dominated research communication, is the idea that the re-presentation of research is acontextual, ahistorical, and apolitical (Carragee & Frey, 2016). By utilising the TUI model in our research communication, we are able to very clearly recognise and pinpoint the contextual, historical and political needs inherent in the messages co-constructed from the voices of the people who are at the centre of a particular research project. TUI provides a way for us to elevate our Māori communities’ voices, to contextualise them and to analyse them with the care and respect they deserve. TUI is concerned with purposefully re-narrating stories to bring about change and regain control of our “data” and stories within our Māori worlds (Allport et al., 2023).

Research and storying through a creative lens

“We have to ask, how can we build and teach the tools and resources necessary for us to thrive in stories that belong to us? How can we learn from stories to weave together just and habitable futures collectively?” (Dutta, 2022, p. 365)

Researchers in academic institutes are often constrained by neoliberal agendas that prioritise economic efficiency and measurable outcomes of research projects (Walsh et al., 2013). Within these academic hierarchies, standard scholarly mediums, such as publications in high impact journals, are often valued over novel forms of creativity (Walsh et al., 2013). Creativity in research and science landscapes holds a contested role, positioned simultaneously as incongruent to scientific innovation, or alternatively, imperative to its advancement. Creative outputs can be seen as risky, expensive, or intangible - where a preference for traditional ‘scholarly’ outputs and research funding reveal the perceived values of academic institutes (Coemans & Hannes, 2017; Vaart et al., 2018). Despite this, interest in creative and arts-based research methods and dissemination strategies is growing, (Boydell et al., 2012; Coemans et al., 2015), alongside an increased focus on research that delivers real-world impact (Health Research Council of New Zealand, 2020).

However, discussions of research impact often fail to acknowledge the diverse ways knowledge is generated and shared across different cultural contexts. From a Māori worldview, where knowledge is historically transmitted through oral traditions, research dissemination is not limited to written reports and academic journals. For instance, waiata (song), haka (ceremonial dance), ngeri (short haka), oriori (chant, lullaby), and other oral and performative forms serve as valid and meaningful ways of transmitting knowledge. Nonetheless, the Western academic paradigm continues to privilege written text as the primary mode of dissemination, and standards for funding reporting on research often don’t align with Indigenous storytelling (Geia et al., 2013). This creates a persistent tension for Māori researchers navigating both systems. This tightrope between Māori and Western knowledge systems reinforces the need for research impact to be defined in ways that honour Indigenous methodologies and worldviews.

Creative based research dissemination strategies can encourage nuanced approaches to data analysis, inspire exploration of multiple meanings of complex sociopolitical experiences and facilitate more engaged relationships between researchers and communities (Vaart et al., 2018). As such, creative dissemination instinctively aligns with Kaupapa Māori approaches to research that value pūrākau (Māori story telling) and critical engagement with social phenomena.

Change in research communication is crucial, as we know that, on an international scale, ineffective research dissemination limits progress in achieving meaningful social improvements (Eljiz et al., 2020). Western norms impose rigid standards on what is considered ‘academic’ (Hikuroa, 2017; Smith, 2021). As a result, Indigenous methods of knowledge collection, interpretation, and presentation are often dismissed as non-scholarly, and shape who can ‘legitimately’ participate within the process of research.

In this way knowledge is privileged when it is reinforced by hegemonic academic credentials, and the legitimacy and value of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledges and science) is minimised (Waitoki, 2022). This limits the involvement of diverse voices and makes it challenging to fully represent our Māori communities. While the growing inclusion of community, whānau (family groupings), hapū (sub-tribes), and Iwi (tribes) - based researchers is beginning to address this gap (Kawharu et al., 2024), we recognise that truly impactful research communication requires a much broader skill set than academic qualifications alone can provide.

A key aspect of our role as Kaupapa Māori researchers is to nurture, develop, and support emerging Māori capability and capacity (McAllister et al., 2022). As an Iwi-owned research institute, we achieve this by actively engaging with Māori students across tertiary institutions in Aotearoa. Capability building here refers to the enhancement of Māori students’ individual skills, knowledge, and competencies that enable them to thrive in academic and professional settings. This involves fostering critical thinking, leadership, cultural competence, and resilience, as well as providing opportunities for practical experiences, internships, and leadership roles. The goal is to empower Māori students to apply their knowledge and skills effectively, both in academic contexts and within their communities. Building capacity refers to the development of resources, infrastructure, and support systems that empower Indigenous students to achieve their full potential. Both processes aim to support Indigenous students’ holistic development and contribute to self-determination and community upliftment, as well as supporting the continued learning of senior researchers who operate in a ‘tuakana-teina’ (older sibling – younger sibling) role of reciprocal learning.

New methodology pathways - Tō mātou kāinga, tō mātou ukaipō

“Evidence needs compelling stories. Compelling stories need new language that moves people to act.” (Dalmer et al., 2022, p. 19)

For this article we use a case study to illustrate the evolution of “data” in collaboration with young Māori creatives by drawing from a recent example of re-working data from one of our research projects called Tō mātou kāinga, tō mātou ukaipō - Whānau conceptions of home: supporting flourishing home environments (Tō Mātou).

The Tō Mātou project is a 5-year research study in Aotearoa New Zealand that explores how Māori understand and experience home in cultural and contemporary contexts. Through interviews with whānau and individuals, as well as discussions with key stakeholders involved in the Māori housing sector, the research seeks to develop a new understanding of ‘home’ that challenges dominant, Western conceptions. The study focuses on how Māori views of home - centring around relationships, place, and space -impact the safety, wellbeing, and aspirations of whānau members. The study aims to reshape discussions about our built environment to better reflect Māori needs and perspectives.

The Tō Mātou research project employed a Kaupapa Māori research methodology, ensuring Māori values and principles guided the research from its design to the dissemination of findings. This methodology was crucial for exploring whānau conceptions of home and home environments that support Māori wellbeing and flourishing. Data was collected using flexible interview approaches that attended to Māori everyday realities or areas of expertise and was analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Findings from the study highlighted that participants described home as deeply rooted in whakapapa and ancestral connections, often symbolised by the grandmother as the central figure holding the family together. Home was more than a physical space; it was a site of cultural expression where taha Māori (Māori identity) could be fully lived. Whenua (land) was central, with participants seeing themselves as kaitiaki (guardians) and expressing a desire for tino rangatiratanga (self-determination) to shape their environments according to collective needs. Home was also relational, grounded in intergenerational bonds and envisioned as a place of safety, healing, and self-sustainability. Participants aspired to be in homes that reflected Māori identity, especially in urban areas, with contemporary papakāinga (traditional home-space) highlighted as one of the ideal models. Ultimately, the vision of home centred on the return to te ao Māori, where rangatahi (young people) and mokopuna (grandchildren) could thrive in spaces of simplicity, freedom, and flourishing.

Amplifying analysis: Creative ways of bringing whānau voices to life

In order to apply the type of creative lens that can take the voices of Māori research participants and represent them in ways that engage, connect and tell stories with reflexive resonance, we reached across to Māori students who are emerging creatives in the fields of writing and design. After the initial analysis of the Tō Mātou transcripts by the researchers, two emerging Māori creatives - students from Auckland University of Technology (AUT) Tomairangi Morgan and Jordan Tane - were brought in to bring novel interpretations from their backgrounds in arts, writing, poetry, creative design, and Te Reo Māori (the Māori language). These young Māori creatives were encouraged to re-analyse and re-interpret the data through their unique creative lenses.

Stories of home

The initial whānau data transcripts were firstly shared with Tomairangi Morgan, a student majoring in Creative Writing and Te Reo Māori (Māori language). As part of this process, the research team held a wānanga (discussion) to reflect on insights from the transcripts. This collaborative session provided an opportunity to delve deeper into the constructed themes and research findings. Inspired by the voices and lived experiences shared by the research participants, Tomairangi was motivated to engage in a creative writing process that honoured their stories through culturally grounded forms of expression. She wrote a series of pūrākau (narratives), including short stories and poems, as a way to weave together her interpretations, emotional responses, and critical reflections on what the participants revealed. These creative pieces were not simply artistic representations but deeply considered responses that allowed her to explore the nuances, silences, and spiritual dimensions of the participants’ perspectives. The use of pūrākau reflects Indigenous methodologies, privileging storytelling as a legitimate and powerful form of knowledge production and meaning-making.

The book Tō Mātou Kāinga, Tō Mātou Ūkaipō: A Collection of Stories about Māori Perceptions of Home was published as a result of Tomairangi’s re-narration of the data.

Artefacts about home

Following the publication of Tomairangi’s narratives, and in collaboration with AUT’s Good Health Design department, the book was shared with Jordan Tane, a Communication Design student who worked closely with Tomairangi to develop a series of artefacts that visually represented the stories within the collection. The words and sentiments expressed by whānau inspired Jordan to consider how design could support the transition into better futures, drawing from the positivity and resilience embedded in their kōrero. Physical artifacts offer a sensory depth that goes beyond a single image. The ability to touch and engage with an object from multiple perspectives fosters a more profound connection, sparking imagination and enabling deeper interpretation. These considerations informed the creation of the four artifacts, ensuring that they not only resonated with Māori but also evoked familiarity and engagement. Rooted in Mātauranga Māori, these interactive elements demonstrated how Indigenous knowledge, when embedded in design, could strengthen connections and elicit meaningful narratives

The artefacts have since been showcased at various events, including the Design for Health Symposium 2023, an exhibition at the Māngere Arts Centre, and also receiving nationwide design awards, where they have continued to spark conversations about Māori perceptions of home and wellbeing.

Discussion - Dynamic Research Data: Moving Beyond Static Interpretation

“[…] we have to ask, how can we build and teach the tools and resources necessary for us to thrive in stories that belong to us? How can we learn from stories to weave together just and habitable futures collectively?” (Dutta, 2022, p. 365)

Transcending the research lens

The way in which research findings are communicated is inextricably bound to the way in which research as a theory and a practice, is approached (Dávila, 2023). This article is suggesting that there are ways to move beyond a reliance on one-dimensional research communications towards dynamic and multilayered interactions in research dissemination. Three specific points that we would like to pick up from this suggestion – and in relation to our case study of the Tō Mātōu project – are about creativity, relationality, and non-linearity.

Creativity in research communication

“The most important thing that can be learned from really creative design is how else communication can be constituted”. (Jackson & Aakhus, 2014, p. 127)

Creativity, is not something that sits outside of us, who we are as people, and where we come from, but instead is part of our identity, which guides our interpretation and response to life. As Māori researchers we have access to a cultural history of creativity as a central component of communication, where “cultural markers of identity are […] closely tied to ancestral knowledge, to specific land areas and natural environs, and to tangible objects and practices that hold and represent concepts of importance to te Ao Māori” (Boulton et al., 2023, p. 308). Creativity - while it can express itself as an ‘action’ that results in an ‘output’ - is part of a worldview where we “negotiate simultaneously [our] past, present and future identities” (Mahuika, 2009, p. 135). Our “institutions of culture” which include practices such as painting (kōwhaiwhai), weaving (raranga), tattooing (tā moko), and carving (whakairo), oratory (whaikōrero), ceremonial call (karanga), and song (waiata) (Boulton et al., 2023), are thus part of an ongoing dialogue with our world and each other. Defining creativity as a lived response and interpretation has been essential to the translation, uptake and impact (TUI) approach to our research. By experimenting with the re-interpretation of research “data” we take that idea into new, contemporary spaces.

Creative expressions of research findings open possibilities for broad engagement. When research findings are shared through a range of accessible creative mediums, they can reach audiences who may not typically engage with academic literature (Dalmer et al., 2022). Creative outputs also encourage reflection, dialogue, and even activism, creating a space where research can inspire action in ways that formal reports might not. Integrating artistic mediums into the research process can elicit emotional responses (or some mindset shifts) and lead to the development of alternative representations and modes of expression that encourage discussion and collaborative storytelling (Jones, 2006).

To go back to the case study of the Tō Mātou project, the starting point for the invitation to the creative students to re-present the voices and findings from the study emanated from the TUI approach, which stipulates that all research communication occurs within multiple external contexts and actors, “which always situates and acknowledges that we are part of a complex, evolving world and part of a collective of people” (Allport et al., 2023, p. 9). The creative lenses applied in translating Tō Mātou “data” into narratives, poems, and visual artefacts enabled new ways of listening to the voices of research participants. These creative approaches brought aspects of their stories to life through writing and design, embedding representations of Māori identity.

Creating and designing as a reflective practice involves the continuous interplay between action and reflection. During the process of creating the different representations of the Tō Mātōu “data” the researchers, designers, and creators engaged in an iterative process where we not only focused on the creation of a product or solution but also reflected on the purpose, impact, and ethical dimensions of our work. This continuous reflection allowed us to have deeper engagement with the voices and stories of the Tō Mātōu research participants. It allowed us to constantly re-discover new aspects of the voices from these new, creative lenses and offered opportunities to refine our understanding as new insights emerged.

The integration of creative expression into research doesn’t diminish the rigor or validity of the findings; rather, it enriches the communication of those findings by engaging people on intellectual, emotional, and sensory levels. This approach recognises that knowledge is not only something to be understood but also felt, experienced, and shared. In this way, creative expressions serve as bridges between research and lived experience, making the findings more meaningful, inclusive, and potentially transformative.

Relationality in research communication

“Radical interdependence refers to the fact that everything is connected to everything else, and everything depends on everything else. That for something to exist, everything has to exist.” (Vodeb & Escobar, 2023, p. 32)

The introduction of this article highlights Kaupapa Māori as a research method that embodies Māori values and worldviews around holistic relationality. Research by, for and with Māori is non-extractive and driven by the acknowledgment of the sovereign status of Māori and our connection to each other through whakapapa, the world around us, the cosmos and the spiritual realm (Cram & Adcock, 2022). The centrality of a relational world is thus a norm in our research approach, and our aims of how and who we communicate with.

The design of research communication needs to be purposefully organised to be non-extractive, ubiquitous and address a specific social context (Vodeb, 2023). This means that there is a need to include skills and viewpoints that reach beyond research, and into other disciplines. Bringing in these skills is part of the “quest for social justice [which] is connected directly to the resources and capacities of collective actors working in concert” (Carragee & Frey, 2016, p. 78). Relationality in this sense means that the Kaupapa Māori research - which centres our relationship to Māori participants, their voices, stories and aspirations, from the outset of the study - evolves outwards into new spaces that include our collaborators, and the new audiences and stakeholders that they bring in from their own contexts.

Within the Tō Mātōu project case study, the young creatives that re-narrated the research “data” from within their skill sets became part of our larger community of thinkers and creators. By engaging with the research data for their own interpretation, they too had to step into relationship with the research participants and their life stories. They also had to step into relationship with us as Kaupapa Māori researchers, and our wider community in which our research centre operates, as well as stepping into relationship with each other as they supported one another along the way. The subsequent dissemination of the book and the artefacts also brought new audiences into relationship. Even now, as both the book and the artefacts are out ‘in the world’ the process of relationality across boundaries means that these visualisations of the data have the potential for new and previously un-imagined networks and assemblages of relationships (Dávila, 2023).

Ultimately, a “more diverse and porous series of smaller transformative actions […] arise through changed understanding among all of those involved” (Pain et al., 2011, p. 187); our words carry whakapapa, create ripples, and shape the relationships that sustain us. Relationality in communication reminds us that our words do not exist in isolation.

Non-linearity in research communication

Research communication can be assumed to follow a linear process, where knowledge is generated, packaged, and then delivered to an audience. However, in practice, research communication is deeply non-linear. Rather than a one-way transmission of findings, it is an evolving, iterative, and reciprocal process that reflects the complexity of knowledge systems and the diverse ways people engage with information.

Data analysis by us as Kaupapa Māori researchers is not the endpoint but rather a point of departure. Multi-directional modes of analysis refer to an approach where various perspectives and methods of inquiry are utilised simultaneously, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of a complex issue.

In the case of the Tō Mātou study, the TUI approach invited the creatives to tinker, play, and test boundaries, transforming the original voices of the research participants into outputs that transcend the expectations of the traditional academy. Crucial to this process is the collective endorsement (by researchers and research participants) for these young Māori creatives to experiment and innovate. In this way the research “data” can take on a life of its own, expanding its reach to new demographics and bridging gaps in knowledge across fields and cultures. Letting the “data” travel on an unchartered path requires a certain amount of relinquishing control of narrow or traditional expectations of research pathways and instead being open to unanticipated outcomes. This perspective on research data questions academic norms and provides an example of how Indigenous methods can lead to innovative, transformative outcomes.

Conclusion: All our stories begin at the end

This article has pondered ways in which research communication, through different voices, viewpoints and multiplicities can make the ‘invisible’ visible, can connect different modes and agents of ‘knowledge production’ and can represent social relationalities (Vodeb, 2023). When our research communication is an intentional social practice in which we navigate the relationship between communication production, meaning and change, and where we interrupt Western ‘norms’ around knowledge production, we are able to open up a conversation about possibilities. Our TUI approach, borne out of our own Indigenous values, aspirations and the theory and practice of Kaupapa Māori research, has given us a platform to disrupt and re-shape, in line with aspirational systems change theory (Johnson et al., 2024).

The TUI methodology is a dynamic and iterative process, wherein the data collected through Kaupapa Māori research methods is reinterpreted by Māori creatives - artists, writers, poets, and designers. This provides the opportunity to grow capacity amongst our emerging Māori creatives to engage in critical thinking around Kaupapa Māori research whilst simultaneously enabling them to interpret, experience, and express the data and analysis in a way that is meaningful to them, and where research participants’ stories take on various forms that resonate with their cultural context and lived experiences. Whether through visual art, poetry, storytelling, or other mediums, these forms offer a rich and diverse representation of Māori knowledge and perspectives.

The case study of the journey of re-narration of the Tō Mātōu study highlights that our research communications need to be cyclical and iterative, relational and context-dependent with multiple entry and exit points. As such, knowledges are constantly living and evolving, especially when we consider the rich history of our Māori narratives, which are revisited, incorporated and celebrated as part of this process, where the end of the story is just the beginning.

Glossary

Using quotation marks around the word “data” in this article highlights the tension between Eurocentric academic frameworks, which often reduce interviews and conversations to clinical, extractive “data,” in comparison to our Kaupapa Māori approach that considers these exchanges with whānau as dynamic, living relationships.

TUI refers to the processes of translation, uptake and Impact. Translation: Transforming research findings into accessible and meaningful formats for Māori communities. Uptake: Encouraging engagement and application of knowledge by whānau, hapū, Iwi, and also stakeholders who can effect change with us. Impact refers to intentionally using the communication of research to drive aspirational, transformative changes, particularly in addressing health inequities of Māori.