Dedication

Ni guicaa jñaa biida

Jñaa bichiá neza lua’

ni rini’ ca beleguí ca

Gudaa ndaani’ diaga riuunda BinnizáMy mother deciphered for my eyes

the language of the stars

She deposited in my ears the language of the Cloud PeopleIrma Pineda, Cándida, (2020)

Introduction

In December 2012, I travelled from Mexico City to my grandma’s hometown Guidxi Guie’/Juchitán (Flower City), on the Pacific coast of the southern state of Oaxaca. It marked my first solo visit and only my second visit in more than a decade. One night, as my family and I were having dinner, I asked my uncle to teach me some words in Diidxazá as I had already exhausted the few words that my grandma taught me a couple days before the journey. Growing up in a family of Binnizá (Cloud people) migrants in Mexico City, I was aware that my jñaa biida’ (grandma) spoke another language.[1] I heard it and was familiar with its sound and musicality, but I did not know what the words meant, and I was unable to speak them myself. It felt as if it was something that did not belong to me, that was only spoken by others: it was a way to be kept out of the conversation.

In a movement that I later found to be naive, I asked my uncle if he was instructed in Diidxazá when he went to the local elementary school in the early 1980’s. He was not. My uncle told me it was quite the contrary, teachers actively tried to eradicate Diidxazá in the younger generations and they penalised those who spoke it[2]. My uncle is a native Diidxazá speaker and the moment he started elementary school his Spanish skills were rather rudimentary leading him to be scolded, ridiculed, and punished by teachers. I had heard similar stories about Indigenous languages speakers who grew up in Mexico City, but I was left aghast to hear that these practices also existed in Indigenous communities where language incessantly sprouts from peoples’ mouths and is a necessary skill to navigate life. Silly me imagined that instruction in local schools would be in Diidxazá to preserve it.

When my uncle was explaining this to me, he mentioned that it was a consequence of Justo Sierra’s (1848-1912) vision of the role of education in the post-revolutionary Mexico (1917-onwards). Sierra was a renowned scholar and political figure during the dictatorship of General Porfirio Diaz (1876-1880 and 1884-1910) and one of the intellectuals of the regime. I could not believe it. Official discourse holds Sierra in a pedestal as one of the precursors of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM)—where I was enrolled as a third semester Geography student. In fact, the main auditorium of my Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, is named after him. I could not reconcile the idea that UNAM, the institution that prides itself in being a guardian of modern culture in Mexico, was related to someone who had actively tried to eliminate Indigenous peoples’ and languages in its modernising nationalist endeavours. Clearly the ideas of what Mexican culture is widely vary across time and political projects, but for most part of the 19th and 20th Century, the presence of the Indios[3] has been deemed a problem. The corollary of this is that the category Indio or Indígena has become “a political battleground” (Lopez Caballero, 2021, p. 125).

Mexico’s modernising endeavours

Historical context

To understand the origin of racist dynamics in Mexico and how this has affected and facilitated the extinction of Indigenous languages, it is necessary to go back five centuries to the Spanish invasion of what is now known as Mexico. For three centuries, from 1521 to 1821 as per official dates, the colonial administration of the New Spain formed a caste society with five main groups: Whites, Creoles, Mixed-race, Indians and Blacks and subsequent combinations, some with very unfortunate names like salta atrás (jump backwards) or No te entiendo (I do not understand you) (Vinson, 2018). Dozens of ethnocultural groups, with their languages and customs, were grouped under the strange category of “Indios.” This category was conceived, and continues to be used in a derogatory, or sometimes paternalistic, fashion (Vinson, 2018).

When Mexico became independent in 1821, Spanish was imposed as the official language to the detriment of non-Spanish-speaking populations. Following the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917), attacks on Indigenous languages and cultures intensified through two interconnected strategies. To reduce Spanish illiteracy rates, the government embarked on Spanish literacy campaigns hoping that Indigenous populations would abandon their languages and adopt Spanish instead. At the same time, it imposed the ideology of mestizaje (miscegenation)—the integration of Indigenous populations to the Mexican society. In 200 years, Indigenous languages speakers have been systematically targeted reducing them from 85% to 6% (Cifuentes, 2002). The Ayuujk linguist Yasnaya Aguilar (2020a) considers that the official mestizaje policy meant to de-indigenise the Indians and language extinction was core to this policy.

The colonial caste system experienced little change after independence. The power shifted from Spaniards to Creoles—people born in New Spain to Spanish parents; the new society kept the former social structures that exploited Indigenous peoples and limited their participation (Gonzalez, 1965). On top of that, the Mexican government actively sought to attract European settlers through an open-door policy. This strategy, most representative during Porfirio Diaz’s dictatorship, followed the idea that European presence would promote development and equilibrate the country’s situation while eradicating Indigenous communities (Alonso, 2004).

Postrevolutionary society

Justo Sierra, the politician whom my uncle mentioned as a responsible for the eradication of Indigenous languages, worked for Diaz’s administration and, among many other intellectuals, upheld the importance of education to modernise the population. Although he did not live to see it, after the Mexican Revolution a nationalistic project of mestizaje was forged by the European-oriented elites, especially Jose Vasconcelos (wryly called Blancocelos[4]), the Minister of Education who launched aggressive Spanish literacy campaigns from 1920 to 1940 (Alonso, 2004). Succinctly, the larger project considered that the mix of Indios and Europeans would create a superior Cosmic Race that would free Indios of their barbarian, traditional, and mystic lives leading them to progress and modernity (Moreno & Saldivar, 2016). Mestizaje was a racial project as much as it was a cultural one. Although the miscegenation ideology proposed mestizos (mixed-race) as the pinnacle of civilization, whiteness remained unchallenged at the centre (Sue, 2013). This mestizaje paradigm has been the bedrock of the Mexican nation in the past century. Despite its negative impact, Brown-skinned Mexicans uphold it and reproduce it because they “achieve a sense of belonging to the [raceless] national community” (Sue, 2013, p. 184). The imagined raceless society has proved to be quite racist since racism has been normalised and acts as an articulating force of the Mexican society (Moreno & Saldivar, 2016). The postrevolutionary ideas of miscegenation are still reinforced by the state through propaganda and education. Towards the turn of the 21st Century, a new paradigm emerged to replace mestizaje: the policy of multiculturalism.

Multiculturalism in Mexico

One of the key moments in Mexican legislation was the constitutional switch to Multiculturalism in 1992. Lopez (2022) argues that Mexico’s approach to multiculturalism aims to normalise and homogenise the Indigenous communities as their existence is contrary to the political, economic and legal ethos of the Mexican nation, (see also Aguilar, 2020a). The Mexican Constitution (2025) states in the second article that “the Mexican Nation is unique and indivisible. The nation is multicultural, based originally on its Indigenous peoples” who have the right to self-determination that will be exercised within the constitutional framework of autonomy that ensures national unity.[5] The constitution is allowing Indigenous communities to operate independently as long as they are not challenging the supremacy and the validity of the country (Lopez, 2022). Subsequently, Indigenous nations in Mexico have achieved little real recognition and their struggles for land-rights, linguistic diversity and autonomy continue to be heavily constrained by the state.

The impact of multiculturalism in Indigenous nations

Yasnaya Aguilar (2020a) criticises the legal framework through which Mexico interacts with Indigenous communities. In her larger critique to the status of how countries deal with languages, Aguilar (2020a, para. 5) highlights how countries are artificial creations often taken as a “original givens” that, through the use of nationalist approaches, ensure the prevalence of the Mexican state. Aguilar highlights that when Indigenous nations did not manage to establish themselves as countries, they were absorbed by countries and are the subsequent denial of the state project; the category Indigenous is not only cultural or racial, it is political; the category mestizo is not only cultural or racial, it is a political one that was aligned to the aspirations of the country (see also Navarrete, 2016).

Andrea Smith (2008) separates the concepts Indigenous nation and nation-states and she argues that Native feminisms can destabilise them. The basis of Indigenous nations is interconnectedness and shared responsibility not only to other peoples but also to the territory. Nation states, what Aguilar (2020) calls countries, are governed through domination and coercion and are sustained by control over the territories. Aguilar (2020a, para 7) argues that one of the most effective methods that countries use to preserve themselves is to make people believe that apart from being countries, they are actually nations. She concludes that “Mexico is a State, not a nation. Mexico is a State that has encapsulated and denied the existence of many nations.” And she further notes “The Mexican constitution is quite telling with respect to the establishment of those equivalences when it announces that ‘the Mexican nation is unique and indivisible.’ If it really were, the decree would be unnecessary” (para 7). The control over peoples’ languages is also a political project of countries/nation-states and Aguilar notes that we should not use the term minority languages but rather minoritised.

Language reclamation as a practice

Contextualising the social and historical foundations of Indigenous languages in Mexico, I return to my personal experience as a Binnizá descendant growing up in Mexico City. When I talked to many of my high-school and university friends and classmates, we all had a similar family history: our families migrated from other provinces (Michoacan, Guerrero, Oaxaca) and settled in Mexico City seeking a better life. Our grandparents spoke other languages and the next generation, our parents, could understand these languages but were not able to speak them, and the third generation, us grandchildren, were aware of the existence of such languages and sometimes understood and spoke isolated words without being able to use this language to effectively communicate with others, let alone understand other epistemologies or have a strong identity to our grandparents clans and ethnocultural groups. The fact that these stories are shared by many people, not only in Mexico but in other settler colonial countries (Donald, 2009; L. T. Smith, 2012; Wolfe, 1999, 2016) as well (Davis, 2017), shows that they are the consequence of a nationalist project rather than isolated events. These stories were mostly discussed among us students during our own time because debates about Indigenous issues from a personal perspective were, and perhaps continue to be, non-existent in our undergraduate studies (Perez & Wynn, 2023).

But how to reclaim our adscription to our grandparents’ groups and tribes and clans if the nation-state is invested in eliminating, disparaging and bastardising them? If the only way they can exist for the state is when they are coopted by it? Mexico constantly prides itself on Indigenous clothes, textiles, languages, rituals and food but it denies Indigenous nations their right to self-determination and instead grants concessions of Indigenous lands so corporations can exploit the wind, water, oil, and minerals (Aguilar, 2020a). Against this homogenising and coopting approach of the state, one of the strategies that can positively impact Indigenous communities are language reclamation projects (Leonard, 2017).

I had been trying to learn Diidxazá on my own and with some materials I bought in Guidxi Guie’ when I first visited in 2012. A few years later, I found an actual Diidxazá course in the Anthropology Research Institute at UNAM and signed up. I went to the first session on a Wednesday and when I went to visit my jñaa biida’ on the weekend, she was slightly offended I was trying to learn it elsewhere and told me she would teach me instead. For the next year or so, I went to her house every week, crossing the massive city in a three to four-hour return journey. But these classes finished when I enrolled in my master program and did not resume. For the next few years, I started speaking Diidxazá with her, keeping my notebook close to me so I could jot down the new words and phrases as I was learning them.

Finding the time to learn and speak Diidxazá is challenging because it does not fall into the category of work or study. Apart from the hours I met with my jñaa biida’ weekly, the language does not exist anywhere else. I do not hear people in the street or in major media outlets speaking Diidxazá, when I talk to people at work, university or when I meet with my friends, the default language is Spanish. When I am not in Guidxi Guie’, apart from those few hours a week with my jñaa biida’ or when I actively choose to listen Binnizá music or read Binnizá authors, Diidxazá is silent, slowly dying, and how can you learn a language if you have no one to speak it with? The moments when I speak or hear Diidxazá are little tingling fireflies suspended in an otherwise dark night. And they exist only because I either create them by talking to my jñaa biida’, because I actively look for them, or because I mutter words, verses and phrases by myself.

One day in 2019 I went to the Rosario Castellanos bookstore in Mexico City’s wealthy Condesa neighbourhood. This bookstore is part of a network of government-owned bookstores and is one of the biggest in the city - home to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of books and titles in several languages. I asked a staff member if they had books written in Diidxazá. The staff member looked at me a bit surprised and went to the computer to look for some keywords. They swiftly came back and pointed me to a small Indigenous literature section and told me maybe I could find something relevant therein. I went to the section that was rather one slightly hidden small-sized shelf and checked a few of the titles only to find that there was nothing in Diidxazá. When I turned around to head to the exit, I stood a moment in that little corner and from there I could see the immensity of the bookstore. I could not help but think that in all that universe of knowledge, in all that enormous and beautiful building, there was not even one book written in Diidxazá. It felt as if many other authors, ideas, topics and perspectives were more important than those of the Binnizá.

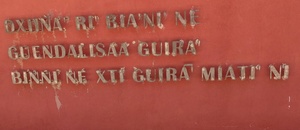

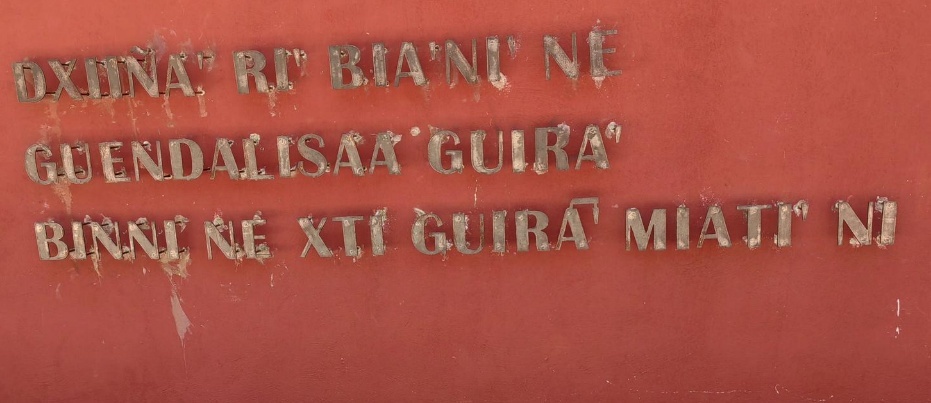

Fast forward a couple years, I arrived at Sydney in December 2019 to study my PhD and I experienced a renewed appetite for learning Diidxazá. I found an online course hosted by local language school based in Mexico City. Diidxazá was offered along English, French, Italian, Russian, and Nahuatl (the most spoken Indigenous language in Mexico) to mention a few. In my view, it gave the language validity, and it felt as if it was equally important and relevant as other Western languages. With the Covid-19 restrictions, the course was online. For over a year, every Thursday morning I joined the sessions that were held on Wednesday afternoons in Mexico City. The sessions were not only about grammar, syntax and verb conjugation, both teachers and students shared their personal stories: why did they want to learn and teach Diidxazá, how their families had lost the language when they migrated, and how they were at different stages in their language-reclamation journey. The teachers often shared with us stories of their families and childhood growing up in Guidxi Guie’ and interacting with the Binnizá poets and scholars in the local Liidxi Guendabiaani’ (Community Centre) (see image 2). Stories also included their journey finding a community of Binnizá migrants in Mexico City. We shared poetry, songs, memories, knowledge about food, and jokes and this all contributed to understanding a different epistemology and, beyond that, to creating a feeling of community among us.

Most of us students had been born elsewhere to migrant Binnizá parents, and, for the first time, we learn to say the names of our hometowns in Diidxazá rather than using the more common Nahuatl or Spanish toponyms. Juchitán is Guidxi Guie’, the Flower City; La Ventosa is Guidxi Bi, the Wind City; El Espinal is Guidxi Gui’chi’, the Thorn City. Suddenly the names became meaningful because we not only learned how to say them, but we also learned why they are named after relevant environmental features. For example, the guie’ chaachi’ flower (see image 3) is used by Binnizá people of the Tehuantepec Isthmus as a ceremonial flower to adorn deities, as an offering in funerary rites and to renowned people but also used for gastronomy purposes to create the bupu (foam), a hot beverage containing cocoa, guie’ chaachi’ and other spices. Ornamental garments often depict guie’ chaachi’ among with many other flowers.

There are two relevant points in the previous story: the use of digital tools, and language reclamation projects. Huilcan (2022) argues that Indigenous communities use digital tools to revitalise their languages and explores how these tools allow people to imagine and create different futures. I want to concentrate on the second idea: language reclamation projects.

There is abundant bibliography related to language reclamation and revitalisation efforts. While some scholars prefer to use the concept revitalisation (Wiltshire et al., 2022) others propose the concept of reclamation. Beyond specificities of academic concepts, some Indigenous communities frame their efforts as language revitalisation (Cru, 2015) while others as reclamation (Gutierrez De Jesus & Chávez González, 2022) projects. Davis (2017) proposes that language reclamation should not be an individual-focused approach comprising only speakers, learners, but should also include larger groups and even communities (people supporting the learners in their journey and people connected to speakers and learners). As McCarty and colleagues (2018, p. 161) state, language reclamation is not about preserving language as an abstract entity, but rather understand language as “an embodied experience of personal belonging and responsibility” that encapsulates connection to the self and the communities we are part of. It is a project looking towards the future of language (against approaches that conceive this as past preservation) and seeks to create a sense of pride in its speakers. McCarty and colleagues also argue that the aim of language reclamation is not to come to an idyllic past of language purity, but to recognise its “dynamic, multisited, heteroglossic, and multivocal character” (2018, p. 161). A central part of language reclamation programs is favouring local epistemologies (Leonard, 2017) because, as, the Puerto Rican scholar Ramon Grosfoguel (2015) argues, epistemicides (the eradication of epistemological knowledge) in Abya Yala (present-day American continent) was key to implant a colonial system and to consolidate Western knowledge as the only valid form of knowledge.

I organise this article around the concept of language reclamation because authors recognise the link between language extinction and coloniality (McCarty, 2021). Language reclamation is a decolonising practice because he links language extinction to a colonising strategy and understands that:

Reclamation is thus a type of decolonisation. Rather than exhibiting a top-down model in which goals such as grammatical fluency or intergenerational transmission are assigned, it begins with community histories and contemporary needs, which are determined by community agents, and uses this background as a basis to design and develop language work (Leonard, 2017, p. 19).

Language is never independent from its environment – as it became clear with the names of the locations and towns I mentioned and there is a close connection between language preservation and land defence as Aguilar argues (cited in Albarran, 2023). One of Leonard’s interlocutors (2017, p. 26) argues that “It’s not just a language” and relates it to land conservation and defence, especially in contexts of increased migration. Fitzgerald (2017) similarly argues that language loss can be deleterious to the overall health of the community because it is impossible to separate language loss to other losses like land, culture and sovereignty. Language is used to name the land and it cannot be separated from it and therefore language loss and land fights are closely intertwined and cannot be separated (Bigelow et al., 2020).

In a similar sense to McCarty (2021; 2018), Yasnaya Aguilar (as cited in Barnils, 2023, para 30) argues that we should not consider languages by themselves; instead languages matter because they represent the epistemologies of the speakers of those languages. In her words:

I care about the languages, I love them, but I care more about the speakers because to disappear a language, you need to subjugate the speakers to a series of oppressions for a long time. When a language dies or is no longer transmitted, the violence [that facilitated their demise] has a long history. Death is the symptom [of that violence].

Aguilar (2016) critiques the official approach to language revitalisation projects, understood as projects implemented by the government (or state) to teach Indigenous languages. Through so-called “bilingual schools” located in Indigenous communities, the state claims to support children’s acquisition of Indigenous languages. However, the schools are considered of lower quality among local inhabitants and often treat the Indigenous languages as a foreign language teaching it a few hours a week. The country’s approach to Indigenous issues is through violence, disparagement and lack of care.

Journey to Yoo Ba’

Before embarking on her journey to Yoo Ba’ (The House of the Death), my jñaa biida’ was avidly looking for a bidaani’ ne bizuudi’ set (ceremonial garments). At the beginning, we all thought she wanted it for her, but we later found out that she wanted each of her three daughters to have a new set for themselves. To buy these garments, we travelled to Guidxi Guie in 2022 and in 2024 with no luck. The Covid-19 pandemic had changed the dynamic of the Binnizá society: workers sewing the bidaani’ ne bizuudi’ sets passed away and the traditional festivities and rituals where women often wear these clothes were halted affecting the local market. Few people were producing them and buying them.

In June 2024, jñaa biida’ and I attended the Vela San Jose - a traditional festival popular among the Binnizá Diaspora in Mexico City. Binnizá people are renowned for their commercial activities—none of which I seem to have inherited—and the Vela San Jose attracted vendors who traded local products hard to find in Mexico City. In the opposite side of the stage, vendors installed their stalls and attendees were checking the products, asking for prices and bargaining (see image 4). There, we met one of my former Diidxazá classmates—Guie’ Xhuuba’—who was selling bidaani’ ne bizuudi’ sets along with headdresses and other garments for men. After my jñaa biida’ and Guie’ Xhuuba’ chatted for a bit about bidaani’ ne bizuudi’ sets, Guie’ Xhuuba’ invited us to her store so my grandma could look at some of the sets and, hopefully, buy one. When jñaa biida’ and I visited Guie’ Xhuuba’ a few days after the festival, she showed us around her store and the sets she had. From the beginning, jñaa biida’ and Guie’ Xhuuba’ spoke in Diidxazá. After we exchanged pleasantries, they started talking business and discussing over the prices, materials, designs and styles. At some point, a plumber arrived at the store to take care of a leaking faucet. Guie’ Xhuuba’ briefly explained to him the problem in Spanish and then returned to talk to jñaa biida’. The two of them were talking while I was listening and petting gu’xhu (smoke), the grey-furred cat.

While we were in Guie’ Xhuuba’s house, I remembered a childhood image where in family gatherings only jñaa biida’ her siblings and cousins who grew up in Guidxi Guie’ spoke Diidxazá; those of us who grew up in Mexico City only spoke Spanish. Back then, the daughters, sons and grandchildren could not understand what the Binnizá were talking about, and we limited to merely interjecting with a few isolated words here and there. But this time was different. I was part of the conversation: I could understand, follow, respond, and even ask questions; I felt more identified and connected to them. I no longer felt extraneous to the sweetness of the Diidxazá that travelled to my ears and that filled my throat and mouth with its distinct taste when I spoke it. I was no longer an outsider but part of the conversation that jñaa biida’ and Guie’ Xhuuba’ were having.

Jñaa biida’ was not able to inherit her descendants the language of the clouds that she adored and cherished so much, but she ensured that her daughters had the bidaani’ ne bizuudi’ sets to adorn themselves with in festive occasions and rituals (see image 5). The language she was born and grew up with in Guidxi Guie’ became a burden once she relocated to the outskirts of Mexico City in the early 1960’s. The restrictions were not only coming from the state apparatus or from Mexico City’s racist and classist society that looked down on migrants coming from Indigenous backgrounds, but from members of her family and community as well. I remember asking jñaa biida many times why she did not pass down the language to her sons and daughters and her response was always the same: her husband did not want their descendants to speak the language because this would undeniably identify them as Indigenous and condemn them to a life of backwardness as the national propaganda of the time claimed. He was afraid that when they spoke Spanish, their accented pronunciation would reveal them as having learned Spanish as a second language, he was afraid that while they were speaking in Spanish, they would momentarily and involuntarily switch to Diidxazá as it probably happened to him. Once, jñaa biida’s husband told her that even renowned and literate Binnizá made this mistake, so the answer was obviously to avoid the transmission of language altogether.

Jñaa biida’s story is not alone. As I mentioned, this experience is shared among many mestizos in Mexico who have grown up in de-Indigenised families and who have lost their languages in only one generation. The loss of languages is not calamity that the state aims to remedy or whose negative effects government policies aim to mitigate; quite the contrary, the state actively engages in eradicating Indigenous languages and epistemologies. Against these homogenising endeavours, Indigenous communities develop resistance strategies to preserve their languages and in this article I explored the efforts that Binnizá people and the diaspora living in Mexico City have embarked on. Language reclamation projects developed from within the communities contribute not only to more people speaking their ancestors’ languages and caring about them, but to creating a sense of identity, not as Indigenous peoples—a colonial category—but as Binnizá or as other endonyms that denote affiliation to a community.

Conclusions

Leonard (2017) calls for the need to nurture the language reclamation paradigm that comprises incorporating community epistemologies. This approach is aligned with Yasnaya Aguilar’s (Barnils, 2023) approach when she claims that what matters is not the languages, but the speakers. If the speakers of a language are killed, discriminated against, and disregarded by the state, what incentives do people have to learn and use them? Language reclamation projects stem from a different epistemology that values community and focuses on identity development rather than on learning and using a language while isolating it from its sociocultural context (see Aguilar, 2020b, on endonyms; and Carlson, 2016, on the category Indigenous as a colonial creation).

My mom did not decipher for me language of the stars, nor she deposited in my ears the Cloud Words of the Binnizá. It is hard to determine whether she did not want to, or she was forced not to, because the state apparatus operates to make Indigeneity something to be ashamed of. It was through community engagement and language reclamation projects that descendants of Indigenous migrants like me can learn, appreciate and cherish the languages of our ancestors. Against the incessant homogenisation of the state, these community projects are a form of resistance that creates community, teaches other epistemologies, and forges a new sense of identity and belonging. Community, belonging and language can light the colonial night - the darkest night.

Guendariuxquixhe / Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to Dr. Innez Haua, from the Centre of Critical Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, for her support and guidance in the 2024 HDR Global Indigenous Internship, to Alana Blakers for their assistance during the editorial process, and to the three anonymous reviewers who read this manuscript very carefully and provided me with valuable feedback.

According to official discourse, Mexico is a multicultural country: there are eleven “Indigenous” language families divided into 68 languages and 364 variants.

See also De Korne and Weinberg’s (2021) work with Diidxazá speakers

Indio (lit. meaning Indian) is an offensive term to refer to Indigenous peoples in Mexico. In tracing the history of the concept, Vinson III (2018) argues that Dozens of ethnocultural groups, with their languages and customs, were grouped under the strange category of “Indios.” Although no longer in official discourse, that has instead switched to the term Indigenous, the word Indio continues to be used, mostly as an insult.

Blanco means White and is a reference of his endeavour to whiten the population that becomes central in his later work.

Terminology is italicised to emphasise how the Mexican Constitution sees Indigenous Nations as their property.

_in_the_southern_state_of_lul__(oaxaca)__zaguita_(.jpeg)

._photography_by_the_author._2024.jpeg)

_in_the_southern_state_of_lul__(oaxaca)__zaguita_(.jpeg)

._photography_by_the_author._2024.jpeg)