Introduction

Māori are tangata whenua, the people of the land, Indigenous to Aotearoa New Zealand (Mutu, 2017). As with many Indigenous peoples within settler states, Māori experience staggering health inequities that link to an over-burden of chronic health conditions and inequitable health care provision and access (Signal et al., 2007). For example, although Māori experience higher rates of chronic nutrition-related conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, Māori are less likely to be able to access the relevant primary care services and be referred for specialist care (Kirkcaldy, 2023). However, Māori who do receive care in these settings report higher rates of racial mistreatment, including racism, and poorer quality care overall (Cormack et al., 2018).

Data is inextricably connected to healthcare services, experiences and provisions (Paine et al., 2021). Data can be broadly defined as any material that carries insight, knowledge, or information (West et al., 2020). Data is and always has been central to Indigenous epistemologies (Kukutai & Taylor, 2016). However, Western data and Western epidemiology systems have been used as tools to collect health data from and about Māori, rather than for and with Māori (Zuberi, 2000). Thus creating what Maggie Walter has termed the 5D’s of Indigenous data: data that focuses on Indigenous difference, disparity, disadvantage, dysfunction and deprivation (Walter, 2016). In relation to food and nutrition data specifically, this research presents the powerful connections that exist between health data, health policy, health professional practice and service provision, and the impacts of these connections on Māori health experiences and outcomes (Cormack, 2010; Paine et al., 2021).

This paper presents work from a kaupapa Māori doctoral research project that positions the historical and ongoing complex interactions between food and data as pathways for understanding and remediating the over-burden of food and nutrition-related health conditions among Māori (Rapata, 2025).

Kaupapa Māori theory is a form of critical theory that is politically grounded and culturally anchored in Māori ways of knowing, being, doing, and seeing (Smith & Smith, 2019). Kaupapa Māori theory in research aims to critique settler colonialism and to transform praxis (Mahuika, 2008). My positioning as a trained clinical dietitian and emerging kaupapa Māori health researcher was essential for drawing on kaupapa Māori as an Indigenous research theory and approach in this work. Which, overall, sought to critique colonial food and data systems and structures, whilst also exploring transformative solutions.

In an Aotearoa New Zealand context, IDS as a concept and movement has been championed by Te Mana Rauranga (Māori Data Sovereignty Network), which has developed definitions and guidelines for Māori data sovereignty and Māori data governance (Te Mana Raraunga, 2018). For example, Māori data sovereignty “refers to the inherent rights and interests that Māori have in relation to the collection, ownership, and application of Māori data.” Māori data governance is “the principles, structures, accountability mechanisms, legal instruments and policies through which Māori exercise control over Māori data governance” (Te Mana Rauranga, 2018).

Informed by the foundational work from Te Mana Rauranga and the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) this paper offers definitions for Māori nutrition data (MND), Māori nutrition data sovereignty (MNDS) and Māori nutrition data governance (MNDG) (Te Mana Raraunga, 2018; West et al., 2020).

-

Māori nutrition data (MND) is any data related to kai, food, nutrition, diet, wellbeing, or food environments that is by, for or about Māori.

-

Māori nutrition data sovereignty (MNDS) implies the inherent right of Māori as tangata whenua to access and control MND in line with self-determined aspirations and needs. Māori nutrition data sovereignty also implies complete control over MND to support Māori peoples, resources, environments, languages and wellbeing.

-

Māori nutrition data governance (MNDG) is defined as the principles, structures, accountability mechanisms, legal instruments and policies through which Māori can exercise complete control over Māori nutrition data

Methodology

The methods and processes used in this review are underpinned and influenced by kaupapa Māori theory, mātauranga Māori/ Māori epistemologies (Reid et al., 2019), whakapapa (Māori ontologies/ Māori ways of being), Māori ways of doing and our own researcher backgrounds (Rapata, 2025). The expression of these methodological groundings can be observed through the centring of Māori data sovereignty principles as well as the foundational principle of mana whakamārama (equal explanatory power) in this review (Harris et al., 2022; Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare, 2002). In the context of this work, mana whakamārama is a grounding in the view that Māori have a right to quality, relevant and non-racialised food and nutrition data to support self-determined nutritional and holistic wellbeing.

This research involved the review and analysis of publicly available information and secondary data and did not involve direct contact with human participants. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Auckland University Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC24064).

Methods

This review had three key phases: (A) survey identification, (B) the development of a kaupapa Māori analysis framework for MNDS and MNDG, and then (C) the survey review using the framework.

(A) Identifying the six surveys reviewed

These six national surveys that collect food and nutrition data from Māori were identified through conversations with Māori data experts. An overview of each survey is detailed below in Table 1, which contains summaries of the history of each survey, the objectives, the nutrition data collected, and the number of Māori represented in each survey sample (Table 1).

(B) Developing a kaupapa Māori food and nutrition data analysis framework

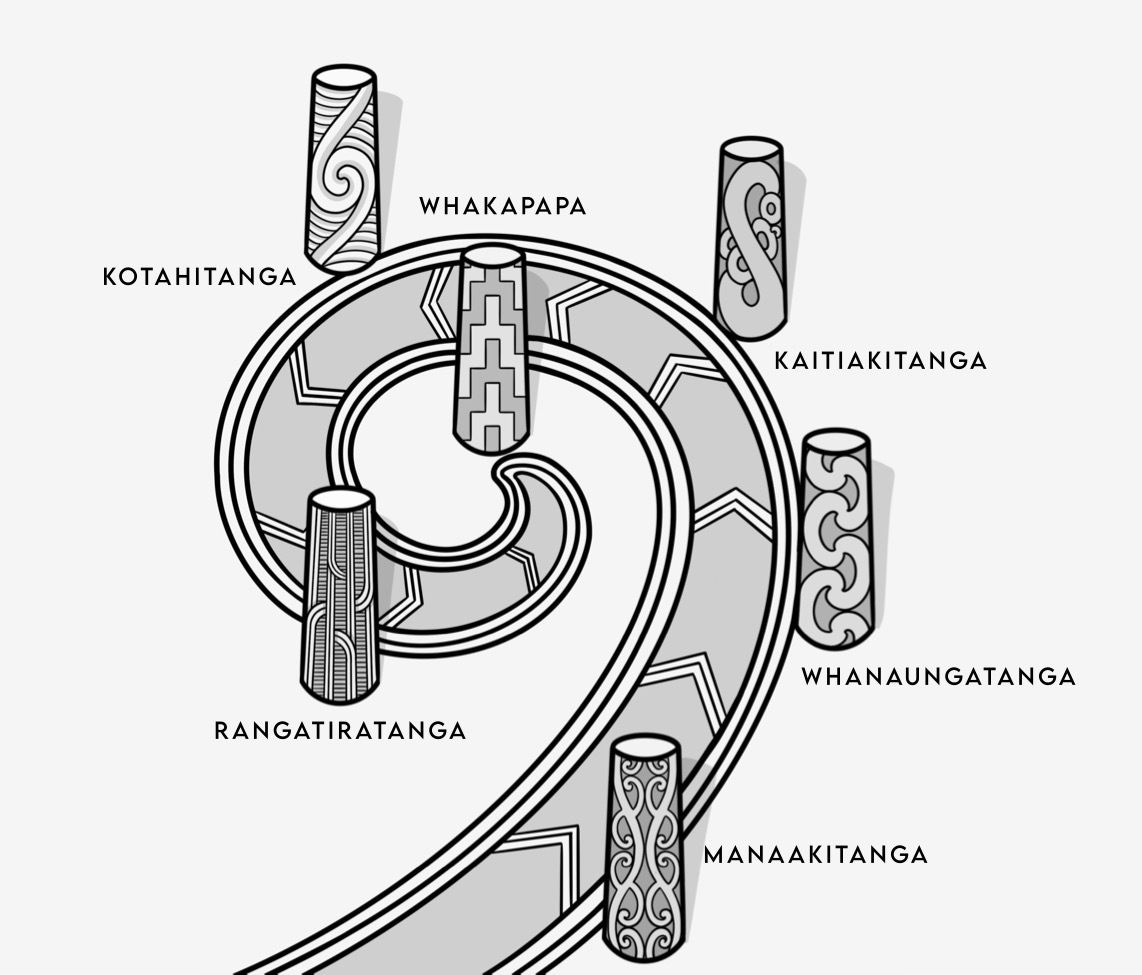

The kaupapa Māori food and nutrition data analysis framework was developed based on the Māori data sovereignty principles and Māori data audit tool from Te Mana Raraunga (Te Mana Raraunga, 2016, 2018). The framework consists of six Māori data sovereignty principles, and was used to guide a critique of past health surveys that include Māori food data. Table 2 further delineates the framework, into the six principles across two main streams: Māori nutrition data sovereignty (MNDS) and Māori nutrition data governance (MNDG). Descriptions of key questions and factors that pertain to each principle are listed in the framework, which enabled the assessment of survey design and outputs against each principle.

This model depicts a pathway with the six Māori data sovereignty and governance principles depicted as guiding pou (poles) on the pathway towards realising MNDS and MNDG for Māori.

The framework developed for assessing the health surveys in this project builds upon the work of Te Mana Raraunga and the Global Indigenous Data Alliance, by extending the concepts of Māori data sovereignty and Māori data governance to specifically analyse Māori food and nutrition data. The framework was developed as an assessment tool for determining how MNDS and MNDG are respected. This framework is also different to the Māori data governance model that was recently released by Te Kāhui Raraunga (Kukutai et al., 2023), as the data governance model provides guidance for system-wide governance of Māori data across public sectors. In contrast, the framework developed in this project is designed specifically for Māori food and nutrition data within specific projects and contexts and was developed before the Māori data governance model was released by Te Kāhui Raraunga.

(C) The survey review using the framework

The framework outlined above was used to review and critique publicly available documents (e.g., published results, websites, methodology reports) from the six surveys. For each framework principle, surveys were reviewed, assessed and scored against whether they met the principles’ criteria under both MNDS and MNDG. Across the analysis, surveys were scored either “one” if a criterion was met, or “zero” if that criterion was not met. Where there are two criteria for a principle, both criteria need to be met for the principle to be met. Therefore, surveys were scored out of a possible 20 points.

As this tool and model are novel, it has not yet been tested or applied in other contexts. The scoring process was conducted by the primary researcher and was subsequently reviewed in detail through supervisory input. Given that the criteria were binary (“yes/no”), there was minimal scope for interpretative variation. Therefore, additional independent or blinded scorings was not considered necessary for this stage of development. The review was completed between March and December 2022.

Results

Table 3 contains a concise summary of the overall review outcomes. For example, for each survey and within each kaupapa Māori principle, the numbered criteria for MNDS and MNDG are depicted. Red squares indicate that the survey did not meet the criteria, and green squares indicate that the survey did meet the respective criteria. Table 3 should be read using the framework in Table 2 and Figure 1 as a guide.

Each survey is scored out of 20 in accordance with MNDS and MNDG using the kaupapa Māori nutrition data analysis framework. These scores are also presented in relation to the percentage to which the survey met the criteria. The lowest-scoring surveys were the Health and Lifestyles Survey and the 2008/09 New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey, which both had a 1/20 (5%) score. The New Zealand Health Survey had the next lowest score with 2/20 (10%). The Te Kupenga post-censal survey had the next highest score with 7/20 (35%), and the Growing up in New Zealand study scored the highest with 9/20 (45%). The Youth19 survey scored the highest with 12/20 meeting MNDS and MNDG criteria at 60%.

Table 4 displays a summary of principled results – that is, the fraction and percentage to which each kaupapa Māori principle was met for MNDS and MNDG across the entire analysis of all six surveys. For principles with two criteria/questions, both criteria had to be met for the principle to meet the overall principle criteria. The percentage score indicates the degree to which each principle was minimally honoured across the analysis of all six surveys.

Where principles were considered, rangatiratanga and kotahitanga for MNDS were the principles most supported across the analysis of the six surveys (33%). With regards to MNDG, whakapapa and whanaungatanga were the most respected principles in practice (33%). However, multiple principles were not evident through the analysis across any of the six surveys; this included whanaungatanga, whakapapa and manaakitanga concerning MNDS. Overall evidence of MNDG across the surveys was poor, as three out of the six Kaupapa Māori principles scored 0 (kotahitanga, manaakitanga, and kaitiakitanga)

Discussion

This research also highlights the intrinsic link between food data, discourse on Māori nutritional health and health professional practice. In addition to issues of consultation versus governance, questioning food assessment and monitoring tools and the complexity of cultural tokenism versus cultural inclusion in national health surveys.

Food data, discourse and health professional practice

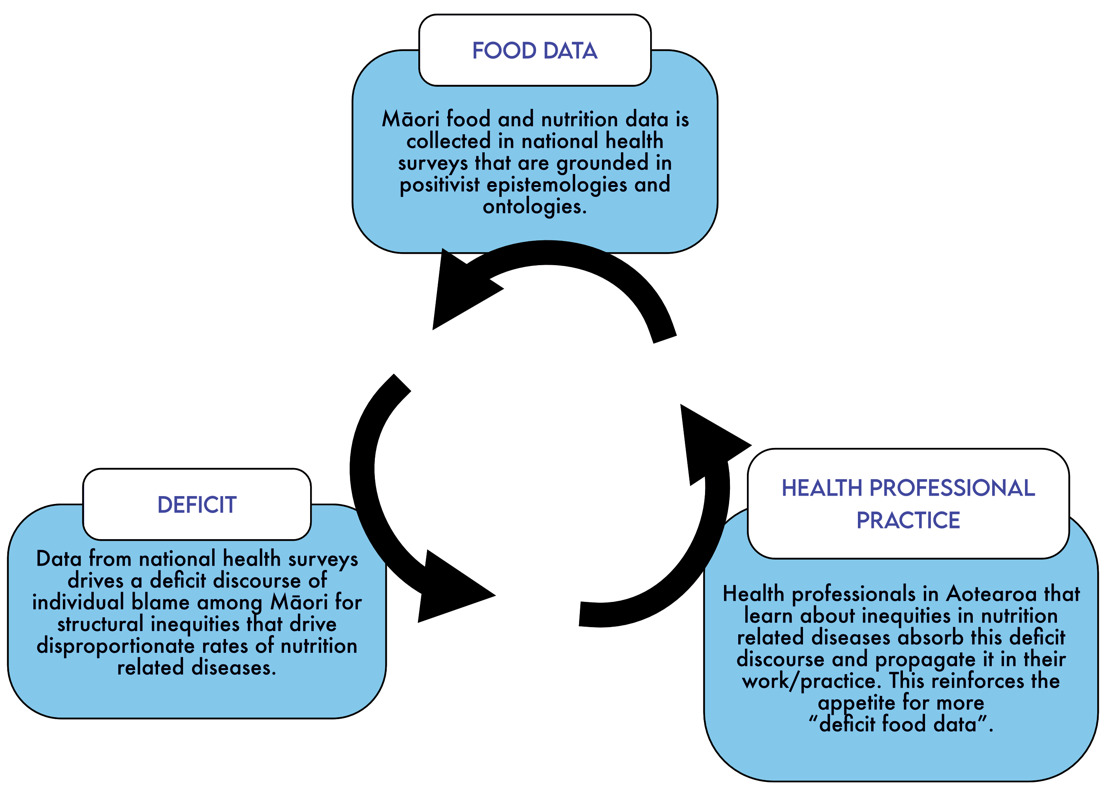

The review demonstrates that when Māori food data is decontextualised, it is likely to support a 5 D’s approach to analysis (Walter, 2016). The problematic nature of these decontextualised 5D narratives has been identified by other Māori researchers, including the work by Isaac Warbrick and colleagues on the biopolitics of biomass for Māori (Warbrick et al., 2016) as well as the work by Ashlea Gillon on fatness and mana tinana for Māori (Gillon, 2020; Gillon et al., 2022). Therefore, while methods, tools and fields of quantitative data collection have evolved, the underlying assumptions across these methods and tools have essentially remained grounded in positivist, colonial ontologies and epistemologies (Paine et al., 2021; Zuberi & Bonilla-Silva, 2008).

The food and nutrition data collected in national health surveys informs clinical standards of practice and nutritional guidelines that form the foundations of Western clinical health, nutrition and dietetics practices in Aotearoa New Zealand (Korohina, 2023). Health professionals can be problematic perpetrators of this individualised, deficit discourse surrounding Māori nutritional health inequities that is created by Western food and nutrition data systems. This is because health professionals, especially those trained in nutrition, dietetics, public health and medicine, are educated in Western nutritional health and diseases based on food and nutrition data, including data from the national health surveys assessed in this study (Hantke, 2022). Therefore, it may be deduced that food data from national health surveys drives a racialised deficit discourse of Māori nutritional wellbeing, which is, in turn, perpetuated by the education curricula and standards of practice among health professionals. This phenomenon is depicted as a positive feedback loop in Figure 6.1.

This phenomenon is evidence of deep-rooted institutional racism in data systems and public health nutrition fields that leads to food data being collected on and about Māori rather than data collected by Māori, for Māori and with Māori. This research asserts that work on decolonising Māori nutrition data cannot be done without humanising the food-data ecosystems that influence health professional practice in Aotearoa New Zealand (Tuck & Yang, 2013). Therefore, the following sub-sections present areas of food and nutrition monitoring that require further advancement to support humanisation and decolonisation in national food-data ecosystems.

Consultation ≠ Governance

Consultation on Māori data issues does not and cannot equate to Māori data sovereignty or governance (Kukutai & Cormack, 2021). Consultation and governance were assessed in the survey review using the criteria associated with the principle of rangatiratanga. Specifically, the explicit visibility of Māori control over Māori data ecosystems was assessed, in addition to the presence of data that aligned with Māori-determined survey priorities. While some surveys demonstrated that they aligned with some aspects of rangatiratanga, there were clear areas where there was no alignment. However, the space between consultation with Māori and Māori data governance is not a linear process (Kukutai & Cormack, 2021). As Tahu Kukutai and Donna Cormack (2021) have stated, “the fullness of Indigenous data sovereignty cannot be realised within the architecture of the colonial settler state” (p.31).

Therefore, it is contended that national health surveys that collect food and nutrition data from Māori could align the survey objectives, methods and methodologies with the requirements of the survey review framework presented in this project to collect, store and produce food data in a manner that is safer and more relevant for Māori. The Māori Data Governance model developed by Te Kāhui Raraunga could also be used to support structural changes and relationship building to better enable Māori involvement to shift more from consultation to governance (Kukutai et al., 2023). However, Māori data consultation cannot be a bridge to fully realising Māori nutrition data governance. Therefore, developing kaupapa Māori food-data surveys and systems is a requirement for working towards MNDS and MNDG at local and national levels. These considerations also led to critiques of the assessment methods often used in national nutrition surveys and the logics embedded in these tools.

Questioning food assessment and monitoring methods

This research questions how relevant and appropriate current food and nutrition measurement and monitoring methods are for Māori, which are concerns that have been raised by other researchers (Korohina, 2023; Shelling, 2024). Common methods of food monitoring and assessment are called dietary assessment tools (DATs) and are designed to be used at individual and population levels to assess nutrient intakes and dietary habits. The data collected using DATs informs clinical health practice, epidemiology research, nutrition guidelines, population health interventions and policies (Cade, 2017).

A recent master’s thesis by Māori nutritionist Erina Korohina sought to understand the barriers and enablers to administering DATs among Māori by interviewing Māori dietitians, nutritionists, and researchers who have training and experience in using DATs (Korohina, 2023). In her master’s work, Erina Korohina articulated that DATs are Western methods for monitoring food intake and nutritional health outcomes from a positivist lens and that inaccuracies occur when DATs are developed and administered from a different epistemological lens to the individuals and populations that fill them out (Korohina, 2023). These inaccuracies in dietary assessment lead to discrepancies between the lived realities of the individuals and populations who are assessed using these methods, and the quantitative nutrition data outcomes that influence clinical decisions, research outcomes and health policies (Korohina, 2023). This critique of DATs is important in the context of national health surveys that collect food and nutrition data from Māori, as these surveys commonly use DATs that have been deemed largely inappropriate for Māori (Korohina, 2023). This indicates that developing culturally informed dietary assessment tools for food and health surveys is a necessary step towards reducing the ongoing reproduction of deficit nutrition data (Korohina, 2023).

Cultural tokenism versus cultural inclusion

A key kaupapa Māori principle in the framework developed for the MNDS and MNDG review is kaitiakitanga. In this context, kaitiakitanga relates to “how data is derived, stored and transferred in a way that supports Māori control over Māori data” (Te Mana Raraunga, 2018). Within the framework, a key consideration for MNDS under kaitiakitanga is whether there is evidence of tikanga Māori, kawa or mātauranga Māori informing the survey protocols, data processing and dissemination.

During the assessment of the six national health surveys analysed in this study, the process of determining the scores for kaitiakitanga revealed a discord between pushing for the inclusion of cultural principles and priorities within national health surveys and the risks of cultural tokenism. For example, the inclusion of tikanga Māori and mātauranga Māori through Māori principles and priorities supports the protection of such data under Māori-led culturally-determined guidelines. However, on the other hand, there is a great risk for documentation and policies for including Māori principles and priorities within health surveys becoming “tick box” items that lead to “non-performative” (Ahmed, 2012) actions, and even worse, the watering down or appropriation of tikanga Māori and mātauranga through the ongoing control of colonial capitalist data systems. Donna Cormack and Tahu Kukutai, in discussing Māori data sovereignty, have described the essence of this risk, being that Māori will be co-opted into supporting and approving our ongoing surveillance (Kukutai & Cormack, 2021).

These are very pragmatic concerns given that many of the surveys in this review are controlled by the Crown, and all of the surveys are organised and led through Crown entities. Therefore, in response to these risks, the structures of data advocacy and activism must be considered to extend the work of Māori data sovereignty as it pertains to MNDS and MNDG without inadvertently propping up cultural tokenism in an effort to support cultural inclusion and data safety.

Conclusion

This review critically assessed the alignment of six national health surveys with kaupapa Māori principles of Māori nutrition data sovereignty (MNDS) and Māori nutrition data governance (MNDG), exposing systemic shortcomings in existing data practices. The findings reveal that the current food and nutrition data systems in Aotearoa New Zealand largely fail to serve Māori aspirations for self-determination, perpetuating colonial and racialised narratives through decontextualised and individualised data framings. Consultation mechanisms, often conflated with governance, fall short of enabling rangatiratanga over Māori nutrition data. Furthermore, the widespread use of Western dietary assessment tools (DATs) underscores an epistemological mismatch that risks misrepresentation and deficit framing of Māori nutritional realities.

Addressing these issues demands a dual approach involving harm mitigation within existing state-run data systems and the active creation of kaupapa Māori food-data ecosystems. Such systems must be grounded in mātauranga Māori, resist cultural tokenism, and support Māori collectives to exercise full kaitiakitanga over their data. This paper ultimately advocates for the use of the MNDS and MNDG framework developed in this project as a tool for reducing the harm of food and nutrition data collected in national health surveys. In addition to developing Indigenous-led methodologies and infrastructures that position Māori at the centre of decisions about how food and health data are defined, collected, and used, in order to restore relational balance and foster genuine nutritional health equity.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge all of the Indigenous and Māori data sovereignty scholars, whose work has been pivotal for informing this project. I also recognise the funders for the doctoral project from which this project has stemmed, these include Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, the Health Research Council, Te Whatu Ora, Te Atawhai o te Ao and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu – ngā mihi nui ki a koutou.

I would also like to acknowledge the support and guidance of Associate Professor Donna Cormack, my primary supervisor during this project, and Dr Erena Wikaire, my secondary supervisor.

Glossary

Aotearoa – Indigenous Māori name for New Zealand

Hapū - subtribe

Hauora - health, wellbeing

Iwi – tribe

Kai - food, meal

Kaitiakitanga – guardianship, stewardship

Kaupapa - subject/topic

Kawa – Māori protocols & etiquette

Kotahitanga – unity, solidarity, collective benefit

Mana – pride, prestige, power

Manaakitanga – respect, hospitality, kindness

Mana motuhake -

Mana whakamārama – equal explanatory power

Māori - Indigenous person of Aotearoa/New Zealand

Mātauranga – Indigenous Māori knowledge

Pou - pole/post

Rarauka/Raraunga - data, database

Rangatiratanga – self-determination

Tangata whenua - people of the land, Indigenous

Te Kāhui Raraunga – national Māori data governance trust

Te Mana Raraunga – national Māori data sovereignty network

Te reo Māori – the Māori language

Tikanga – Māori customs and protocols

Tinana – physical body

Wairuatanga - spirituality

Whakapapa – heritage, genealogy

Whanaungatanga – kinship, social connectedness